At the time of its inception, the Marinid dynasty governed Morocco, then recognized by the enchanting epithet Maghreb Al-Aqsa, the Distant West. This Zenata Berber-origin dynasty earned renown for adorning Morocco with medersas, these Quranic schools. It was under their reign that what historians term the cycle of zaouïas began in Morocco. Through the proliferation of these religious institutions across all territories of Morocco, it signaled the decline of the political authority’s monopoly over religious authority, and conversely, the ascent of zaouïas to a legitimate political function.

The Marinid Sultanate was a Berber Muslim empire from the mid-13th to the 15th century which controlled present-day Morocco and, intermittently, other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian Peninsula (Spain) around Gibraltar.

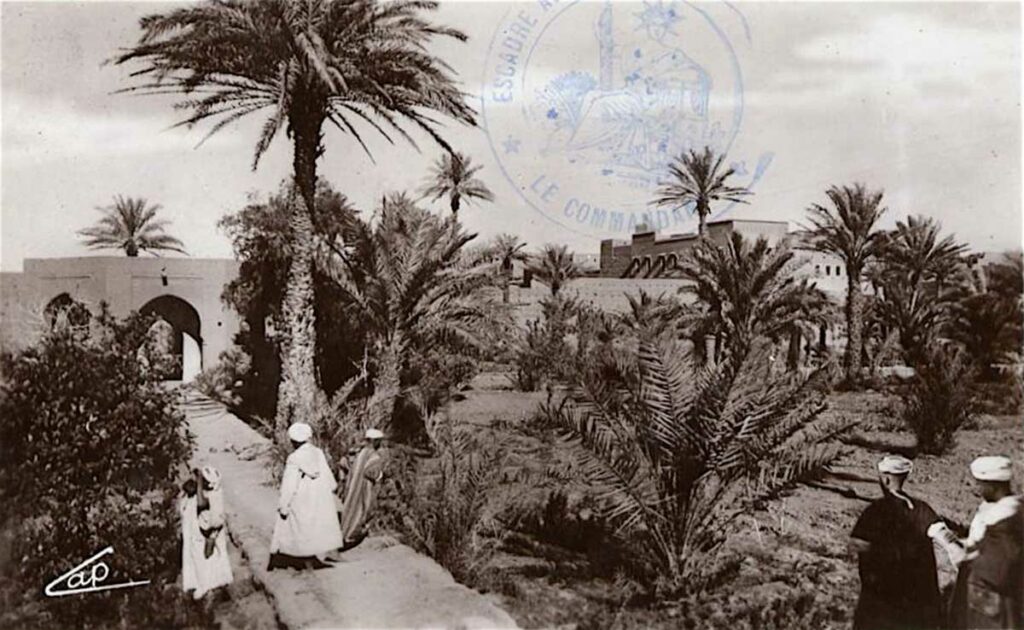

The zaouia of Tamegroute, like many others in Morocco, cannot be solely confined to its religious and mystical character, as it played a significant role in the Drâa Valley and subsequently inspired the establishment of numerous other zaouias bearing the same name throughout Morocco. The spiritual dimension of its identity thus early on complemented itself with a temporal dimension characterized by power, influence, and authority—attributes that are distinctly terrestrial, clearly materialistic, and fundamentally human.

In 1883, the French explorer Charles de Foucauld became the first to venture into the depths of Morocco, documenting in his work “Reconnaissance au Maroc” his impressions upon encountering the zaouia:

« The power of Sidi Ben Nacer is immense throughout the Oued Drâa Valley, the Sous Valley, and the valleys of Oueds Dàdes and Idernis; it extends to Tatta and Agadir Irir in the West and halfway to Tafilelt in the East. (…) Pilgrims come to Tamegroute from even farther away, from Mogador, the Sahel, and Tafilelt. (…) The Sultan consistently shows the utmost respect for this saint on every occasion. »

Charles de Foucauld – 1888

The Naciria Zaouia, now a national cultural heritage, is the result of a tumultuous human adventure whose narrative, woven with conflicts of interest, ambitions, and passionate pursuits of the protagonists, as well as the capricious play of circumstances, resembles the classic and almost romantic framework found in all epic tales that fill the history books of our humanity.

The birth of a zaouia on the caravan route

It was in 1575 that a man named Abou Hafs Omar Ben Ahmed El Ansari settled in Tamegroute to establish the zaouia later known as Zaouïa Naciria.

His journey to reach there was only a kilometer, as he hailed from a neighboring ksar where his ancestor, Sheikh Ibrahim Ben Mohamed Ben Ahmed El Ansari, had already established a zaouia called Zaouïa Sidi En-Nass two hundred years earlier, which translates to the zaouia of the Lord of the people, paying homage to the Prophet. Another French explorer who reached Tamegroute in 1904, the Marquis de Segonzac, described this sheikh in his mission report titled “In the Heart of the Atlas” as a hermit whose sole intention was to live unknown.

No one knows why Abou Hafs Omar decided to establish his own zaouia instead of continuing his religious journey in the footsteps of his ancestors. Marcel Robin in 1918 offers the following explanation in his exploration report:

« Branching out is common in the history of zaouias. The reasons are varied: conflicts among members of the same maraboutic family, excessive proliferation of members in a family that the resources of the mother zaouia can no longer support, the ambition of a family member who feels capable of exploiting their personal baraka for individual gain. »

Marcel Robin

It is worth noting that the zaouia Sidi En-Nass was indeed nestled in a ksar hidden amidst the palm trees, an environment that best suited its mystical intention, whereas Tamegroute was already at that time a thriving village situated on the caravan route from sub-Saharan Africa to the major cities in the North. The ambition of a new zaouia could not have found a better setting to take flight than in such a place of convergence for people and wealth.

It’s crucial to bear in mind that this period is truly the golden age of zaouias. The Drâa Valley was teeming with local brotherhoods, each organizing itself with its own zaouia: the Zaouia of Tagmadarte, that of Tanmslat, the Zaouia Essalhya of Tagounite, or that of Tamnougalte.

The initiative of Abou Hafs Omar Ben Ahmed El Ansari proves successful: the zaouia takes shape in Tamegroute and gains the expected respect. Upon his death, his pious daughter, Lalla Mimouna, assumes the responsibility of managing affairs within the nascent zaouia, overseeing the collection of revenues and organizing social activities that, at that time, involved accommodating and providing sustenance to students, known as Tolbas, as well as guests of the zaouia such as pilgrims, passing travelers, traders, and all the destitute or sick individuals who found refuge and security within the sacred walls of the zaouia.

Beside Lalla Mimouna, a man named Sidi Abdallah Ben Houceine El Qebab, also known as Erraqi due to his family origins on the banks of the Euphrates in present-day Iraq, is appointed as the spiritual master of the zaouia of Tamegroute. He himself hails from the zaouia of Sidi Ennas, but his journey in Sufi initiation, along with the teachings received directly from Sheikh Al Ghazi of Sijilmassa, has bestowed upon him a distinctive aura of sanctity. Marcel Robin’s account narrates that

« The baraka of Sidi Abdallah had the particular virtue of granting male offspring to husbands whose wives were sterile or only bore them daughters, or to those whose children perished at a young age. »

Marcel Robin

Ahmed Ben Ibrahim El Ansari, faithful to the teachings of his master, lived a life of piety and detachment from the material pleasures of life. In doing so, he reinforced the spiritual influence of the humble zaouia of Tamegroute, one among many, but whose fame and power would suddenly reach a definitive milestone through the intervention of his next master, coming from elsewhere.

M’hammad Ben Nacer, the key figure in the destiny of the zaouia.

It was thirty years earlier, in 1603, that M’hammad Ben Nacer was born in the Casbah of Aghlane, in the palm grove of Ternata near Zagora, itself located in the Drâa Valley. His father, Mohamed, also led another modest zaouia and was a revered man due to his claim of Sharifian descent, meaning his genealogical lineage with the Prophet through a chain of ancestry connecting him to Jaafar Ibn Abī Tālib, the brother of Ali, the fourth caliph, and son of Abou Talib, the paternal uncle of the Prophet. The family legend recounts that the name Nacer was bestowed by Jaafar himself.

The young M’hammad receives from his father the initial principles of religious education, and he continues his learning at the mosque of the ksar of Tissergate. At the end of this training period, he attains the title of faqih, signifying that he is regarded as a jurist, well-versed in the rules of Sharia.

M’hammad then takes his first position as a Quranic school teacher in Eldjorfa in the Dadès Valley. He later returns to his native village to teach at his father’s zaouia and is appointed as the imam, meaning the speaker of the holy book, and a teacher in the main mosque. At the age of 26, he has already established a reputation as a meticulous scholar throughout the Drâa Valley. He has significantly expanded his theological knowledge and understanding of Muslim jurisprudence.

However, the journey of this young imam is just beginning. M’hammad indeed feels a fervent desire to assert himself, and his first choice, in the logical continuation of his path, is to deepen his practice of Sufism. As tradition dictates, he embarks on a quest for a master who can teach him and enable him to become part of a maraboutic lineage. He decides to join the zaouia of Tamegroute, just a little downstream from his village along the Oued Drâa. He knew that in these places were the figures holding the most powerful spiritual auras of the moment: the sheikh of the emerging zaouia from Mesopotamia, Sidi Abdallah Ben Houceine El Qebab, and his disciple, Sidi Ahmed Ben Ibrahim El Ansari, the son of Lalla Mimouna.

Thus, in 1631, a young imam and aspiring Sufi left his small zaouia in Aghlane to settle in Tamegroute. Ten years later, despite his reputation, the sheikh of Tamegroute was assassinated during a pilgrimage return to Sijilmassa.

At this decisive moment in its history, the zaouia of Tamegroute had to choose a worthy successor for this title. It happened that only M’hammad Ben Nacer, then thirty-eight years old, had the profile of a charismatic leader. He had quickly become the favorite disciple of the master of the zaouia who, according to tradition, designated him as his successor at the head of the brotherhood by entrusting him with the responsibility of taking care of his children and his wife, Hafsa Al Ansari, meaning to take her as a spouse, after his death.

The grafting of surnames was about to take place, and the zaouia of Tamegroute would erase the name Al Ansari to become the Zaouïa Naciria.

This episode is narrated to us by a 17th-century Moroccan historian, Mohamed El Saghir El Ifrini, who bases his account on the statements of Hosein Ibn Nàcer, the Sheikh of the Zaouia of Aghlane and brother of M’hammad Ben Nacer. The reality is undoubtedly more complex, and the assumption of the official leadership of the zaouia proved to be more challenging than anticipated, only becoming effective five years after the death of Sheikh Ahmed Ben Ibrahim El Ansari.

Despite the last wishes of the deceased sheikh, M’hammad Ben Nacer indeed faced opposition from some members of the zaouia who were reluctant to see a foreigner become the master in their house. Jacques Berque recounts in his work Al-Yousi that a violent offensive by the El Ansari clan was launched against the zaouia, which was in the process of coming under the authority of the Ben Nacer. Faced with this hostility, M’hammad made the decision to return to his original zaouia in the village of Aghlane, taking the widow Hafsa with him.

The official history, narrated through the words of the brother, justifies this withdrawal by citing the statements of Sheikh Ahmed Ben Ibrahim El Ansari himself, attempting thereby to erase the affront of such unflattering oppositions to his prestige:

« Before he died, he entrusted him with the affairs of the zaouïa, instructed him to marry his own wife, and not to deliver the *ouard until receiving a clear order and authentic permission from his master, Sidi Abdallah Ben Houceine El Qebab. He also said to him, “You will live in Aghlane.” (…) Later, M’hammad Ben Nacer contracted a leg disease; the ailment persisted and worsened to the point of completely preventing him from standing or sitting (…). One day, while we were at the bottom of the house, we saw him descend the stairs and walk as if nothing was wrong. We asked him: What is this, O Lord? He said: During my sleep, I saw Master Abdallah Ben Houceine, may God have him in His grace; he came to me, took my hand, and stood me up; then he told me to lead the prayer. So, I stepped forward and led the prayer in front of him and his companions. »

Mohamed El Saghir El Ifrini

Ouerd is the ability to give Sufi initiation to others.

M’hammad Ben Nacer returned to Tamegroute with his head held high, adorned with the marks of his ordeal and dreams. Later, he married the widow Hafsa, thus uniting their names for eternity. However, it took another dream, dreamt by Hafsa, for her to set aside her own reservations and finally accept this marriage.

This profound transformation of the zaouia’s identity, thanks to M’hammad Ben Nacer’s rise to power, followed the usual script of all these human dramas that sometimes serve as the crucible for great individual destinies. Here in Tamegroute, all the ingredients were brought together: the right place where the ambition of an exceptional character settles, a marriage that allows inscription into a respected lineage, adversity in attaining power and a retreat before a victorious return, premonitory dreams, a miraculous healing, and a charismatic personality capable of combining piety and knowledge in one individual.

The zaouia of Tamegroute will now be known as Zaouïa Naciria, the headquarters of the Naciryyne brotherhood. And this title has been passed down to all its descendants until today.

This foundational pattern would later be complemented by strategic alliances with Berber tribes that controlled various parts of the Southeastern territories, a region not yet subjected to the central authority of the Sultan. The future Sheikh M’hammad Ben Nacer, along with his successors, would establish both distant and respectful relations with the Sultans, allowing them over the centuries to serve as intermediaries between central power and the tribes. It would happen that harkas, chérifian military expeditions in the South of Morocco, were accompanied by a naqib naciri, one of the sheikhs of the numerous Naciria zaouias, serving as a political advisor to the expedition leader for negotiating with the tribes.

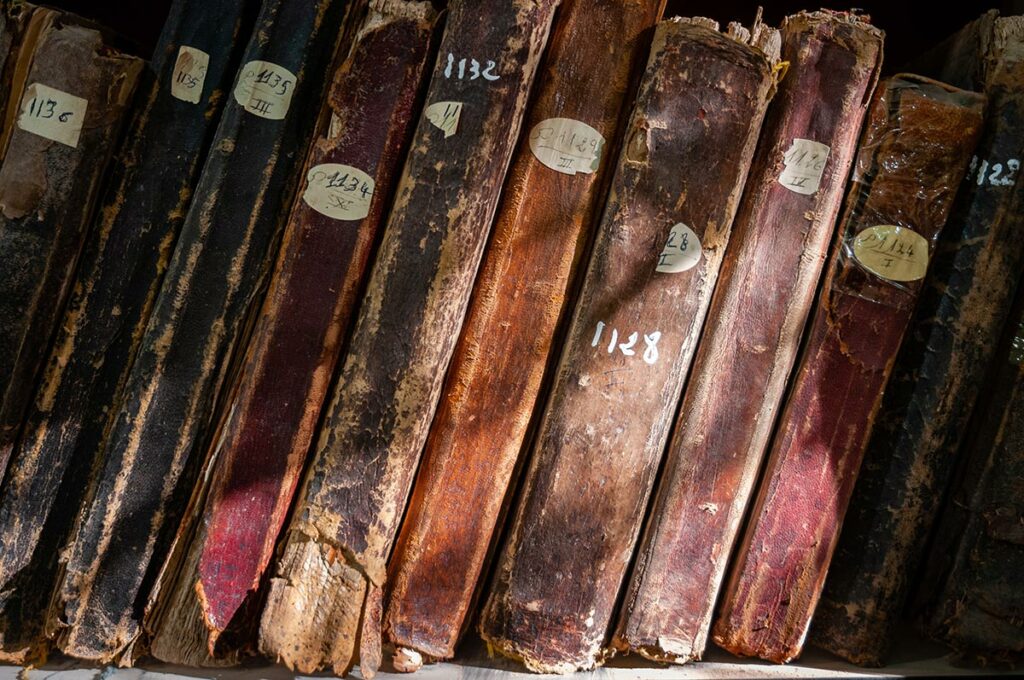

Sheikh M’hammad Ben Nacer transformed his zaouia into a radiant center of Sufi culture. In the 17th century, one of his successors, Ahmed Naciri, established a library within the Zaouïa Naciria. Consequently, the Zaouïa Naciria became a beacon of light not only in Morocco but also in Africa, attracting scholars, religious scholars, and students in search of knowledge who were drawn to the precious works gathered there. The hamlet of Tamegroute became a crossroads for commercial caravans, and the zaouia developed its connections and influences in the region.

Sidi M’hammad Ben Nacer successfully underwent the transformation, leaving a lasting legacy of his name and his zaouia. Upon his death in 1674, he was laid to rest near the entrance of the Zaouïa Naciria, in a mausoleum now known as the Garden of the Sheikhs, paying homage to the line of wise Sufi leaders who, through generations, wove the history of Morocco.

– La zaouïa de Tamegroute – Marcel Dodin – Archives berbères – 1918

– Au coeur de l’Atlas – Marquis de Ségonzac – 1904

– Sainteté, pouvoir et société : Tamgrout aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles – Abdallah Hammoudi – 1980

One Response

Very interesting article. It is great to have registered this Zaouia as part of the national heritage. However, it would be urgent to seriously protect the works of the library, which are kept in conditions unworthy of their quality.