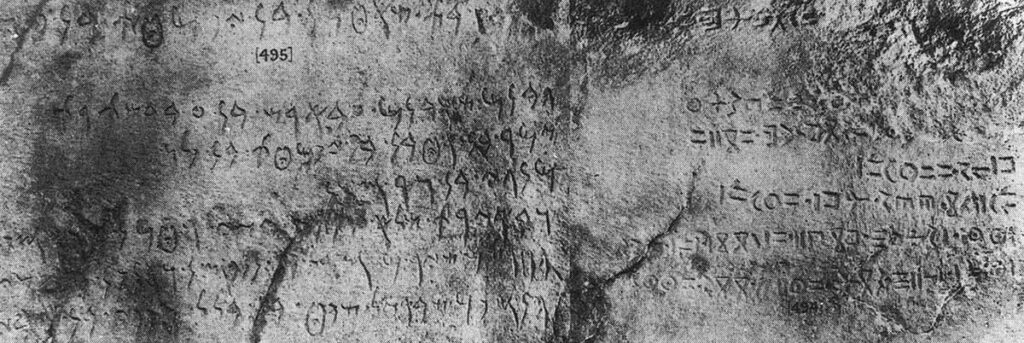

It is one of humanity’s earliest writings, but its origin is subject to various explanations that draw on Egyptian, South Arabian, Greek, Iberian, or Phoenician roots. To date, and just like the exact origin of the Berber people, no thesis has conclusively settled these debates, which in themselves illustrate the dimension of mystery carried by the Berber world.

What is certain is that the existence of Tifinagh, formerly known as the Libyan script, has been attested by scientists since antiquity, and later during the Punic and Roman periods. This is notably visible on funerary monuments and concerns a vast territory stretching from the Mediterranean to the south of Niger, and from the Canary Islands to Libya.

Although the use of this alphabet disappeared early on, the Tuaregs, tribes of the Sahara Desert, are the only contemporary Berber-speaking people to have retained a living practice of writing in Tifinagh.

To better understand this topic, southeast-morocco.com has enlisted the knowledge and experience of Ahmed Skounti, a specialist in these matters in Morocco.

Ahmed Skounti – The debate on origins is rarely ‘definitively’ closed. Science is relative; its conclusions are accepted until proven otherwise, unlike belief, which is absolute and final. The allochthonous origin of Tifinagh was proposed by early researchers in the 19th and 20th centuries. For over two decades now, the idea of an indigenous origin has begun to gain ground.

AS – The Libyco and Tifinagh scripts are two variants of the same alphabet. Each of them includes geographical sub-variants. The term “Libyco” was used by early researchers to refer to inscriptions discovered in the northern part of North Africa, particularly in ancient archaeological sites like Volubilis in Morocco, Tipasa in Algeria, and Dougga in Tunisia. This term is also used in the formula “Libyco-Berber inscription” to describe writings associated with engravings and paintings found in rock art sites across the Saharan and sub-Saharan regions of North Africa.

The term “Tifinagh” was originally used more specifically in connection with inscriptions of the Tuaregs, an Amazigh people whose territory spans Algeria, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Libya.

These two terms, “Libyco” and “Tifinagh,” are merely designations given by researchers, and there is no need to speak of a transition from one to the other. However, the word “Tifinagh,” which has remained in use among the Tuaregs, deserves attention. Some believe it originates from a root “FNGH/FNQ” that is linked to Phoenician.

AS – At present, we do not have precise datings to determine the earliest expression of this Amazigh script. Gabriel Camps suggested that the inscription from the Azib-n-Ikkis site in Yagour, Western High Atlas, could date back to the 5th-7th centuries BCE. In 2012, together with Moroccan and Italian colleagues, we published the dating of the paintings in Ifran-n-Taska, in the eastern Bani. Three samples provided the following approximate dates: 7th, 5th, and 3rd millennia BCE. The lowest, dating to the 3rd millennium BCE, corresponds to the first millennium BCE. The dated paintings are associated with a few painted inscriptions. However, as we did not collect a sample from the painted script itself, we do not know if the painted inscriptions date back, like the dated paintings, to the 1st millennium BCE. We are left to assume so, but it is clear, in any case, that this script is very ancient.

One of the few texts dated precisely is the bilingual Punic/Libyco dedication to King Massinissa dating back to 139-138 BCE. It is likely that future research will shed more light on this subject, provided that archaeological research is further encouraged.

Massinissa : (238 BC – 148 BC) was an ancient Numidian king best known for leading a federation of Massylii Berber tribes during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), ultimately uniting them into a kingdom that became a major regional power in North AfricaNumidia : Numidia was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia and Libya.

The Tifinagh is still waiting for its Champollion.

AS – It is difficult to answer these questions. While relatively recent Tifinaghs in Tuareg environments can be deciphered, the same cannot be said as we move further back in time. Inscriptions from ancient archaeological sites have revealed a few rare secrets, such as the inscription from Dougga, which informs us about the political organization of ancient cities.

It appears that, much like the language, which has several dialects in the Maghreb and Sahara, the writing system differentiated from one region to another. In the north, at least two alphabets have been identified: Eastern Libyan and Western Libyan. In the south, in addition to the four Tuareg alphabets, there are other Saharan or sub-Saharan alphabets, such as the alphabet of Foum Chenna, of which we identified the 33 characters in the book “Tirra, aux origines de l’écriture au Maroc” that my late colleagues Mustapha Nami, who has recently passed away, Abdelkhalek Lemjidi, and I wrote at the beginning of the millennium. This book was the first publication of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) in 2003.

Dougga : Dougga is an archaeological site located in the north-west of Tunisia. It was placed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1997 and is renowned for its well-preserved monuments and the rich history of its Libyan, Punic, Numidian, Romano-African and Byzantine past.

On a diachronic level, it is highly probable that the successive transformations of Amazigh dialects make it difficult to decipher an earlier, now disappeared state. Additionally, the consonantal nature of the script does not facilitate decryption attempts. Finally, North African cooperation is necessary. With the technological means available today and by pooling efforts, it is possible to advance knowledge in this field. Recognition of Amazigh in Morocco and Algeria should contribute to this endeavor.

In short, this script still awaits its Champollion!

AS – It appears that the predominant uses of ancient Amazigh writing remained marginal in a society that did not experience the emergence of central political power endogenously. The Numidian kingdom stands as an exception, as it elevated Amazigh writing to an official script alongside Punic (Phoenician) writing. The previously mentioned Dougga inscription attests to this. Other ancient Moorish kingdoms, principalities established after the Romans, and medieval empires that arose within the framework of Islam do not seem to have employed this script. Even its usage outside central power circles narrowed and disappeared before the Muslim conquest.

Tifinagh continued to be used in the Tuareg region. In the Sahara and the Maghreb, it appears that the symbolic foundation from which Tifinagh originated continues to be utilized in various crafts (weaving, pottery, jewelry, etc.).

Furthermore, while orality indeed dominates the modalities of Amazigh culture transmission, Tifinagh writing was not entirely absent in ancient times. However, more recently, authors have often used other scripts, particularly Arabic and Latin. Since the 11th century and especially in the 18th century, writings in Amazigh have employed the Arabic script, such as “L’Océan des pleurs,” a treatise on Maliki jurisprudence by Mohammed Al-Awzali (died in 1749).

Activists of the Amazigh Cultural Movement have also utilized the Arabic script to write poetry, short stories, or novels. Academician Mohamed Chafik used it for his three-volume Arabic-Amazigh dictionary. The Latin script has also been used to transcribe Amazigh since the 19th century. It has also been adopted by activists of the Amazigh Cultural Movement to write literary creations or transcribe oral texts. These two scripts, Arabic and Latin, continue to be used today despite the adoption of Tifinagh-IRCAM since 2003 as the official script of the Amazigh language in Morocco.

A lire : A dinosaur slumbering in South East Morocco

AS – It is difficult to predict the future of social and cultural phenomena. Since 2003, Tifinagh has been established as the official script of the Amazigh language. In 2011, the Constitution recognized Amazigh as an official language alongside Arabic. In 2019, the organic law concerning this official status was finally adopted. It defines the areas of mandatory use of Amazigh according to a staggered implementation schedule. Amazigh transcribed in Tifinagh has been taught in public schools since 2003. Although its progression and territorial extent remain modest, it enables the dissemination of the language and, more profoundly, a reconciliation of Moroccans with their identity, whether Amazigh-speaking or Arabic-speaking.

However, schools, from primary to university, need textbooks to teach Tifinagh. It is therefore important to transcribe oral literature and encourage literary and artistic creation in Amazigh expression or inspiration to instill in learners a taste for a language undergoing gradual rehabilitation.

The survival of Amazigh as a language is nothing short of a miracle

AS – Tifinagh is undeniably a specific trait of Amazigh culture. Emerging from the depths of ages and recently undergoing Unicode standardization, which allows its integration into various computer platforms, the future of this simple and original script is still long ahead.

AS – The oral language itself is an Amazigh singularity. Contemporary with powerful languages such as Greek and Latin, having coexisted with Arabic, a powerful liturgical language, and living today alongside international languages such as French, Spanish, and English, its survival can be likened to a miracle.

When the 2014 population census announced that 28% of the 34 million Moroccans spoke one of the three dialects of Amazigh, alarm bells rang. But it seems that they were not heard loudly enough. While it is true that Moroccan Arabic speakers are also, anthropologically speaking, Amazigh, the loss of this millennia-old language would be highly detrimental to Morocco and to cultural diversity on a global scale.

AS – I would like to pay tribute to my friend Mustapha Nami, who passed away on February 4, 2020. Coming from Aït Ihya Ou Atmane (Goulmima) in our Drâa Tafilalet region, with his passing, Morocco loses a researcher and a highly valued professional.

In addition to his research in prehistory, rock art, and the history of Amazigh writing, he coordinated the preparation of several submissions of Moroccan elements to be inscribed on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. The last submission he was working on in this field concerns the knowledge and know-how related to khettaras. I hope that it will be completed by the partners with whom he was preparing it so that it can be submitted to UNESCO.

Mustapha contributed greatly to his region, and it would be desirable for it to honor his memory by preserving it.

Ahmed Skouti was born in Timatdite (Assoul) in the High Atlas Mountains, now in the province of Tinghir. He is currently a Professor of Higher Education at the National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage (INSAP, Rabat) where he teaches anthropology and cultural heritage. He holds a doctorate in anthropology from the School of Advanced Studies in Social Sciences (EHESS) in Paris and is also an expert in cultural heritage at UNESCO. He has written several texts in the fields of anthropology, heritage, history, culture, literature, and rock art.