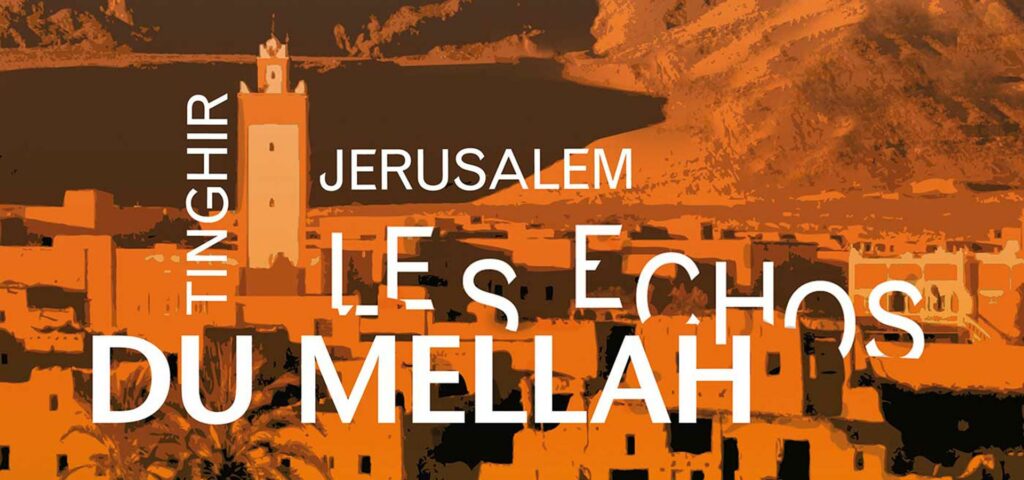

Legend or historical fact? The once-hidden presence of a Christian princess within the walls of the Aït Ben Haddou ksar is supported by tangible evidence that cannot be ignored. Southeast-morocco.com conducted its own investigation to determine whether the most visited site in southeastern Morocco—an iconic showcase of traditional Amazigh earthen architecture—may, in fact, have roots that reach far deeper into history than commonly believed.

Charles de Foucauld has just crossed the Telouet pass, one of the rare points through this veritable mineral partition, that cuts Morocco in two.

In order to venture into this insecure area, where solely the law of the Amazigh tribes prevails, he has donned the clothing of a Jewish traveller, and his guide, Rabbi Mordecai Aby Serour d’Akka, accompanies him, bringing with him his long experience of exploration which, in particular, allows him to enter the Berber villages unheeded, thanks to their Jewish communities. Indeed, at the end of the 19th century, it seemed to Charles de Foucauld more judicious to travel under the guise of a people who, although both accepted and discredited, had been present in these lands since ancient times. This way he was unlikely to attract attention, rather than in the style of a European, who would necessarily be perceived as a Christian; that is, as a possible enemy.

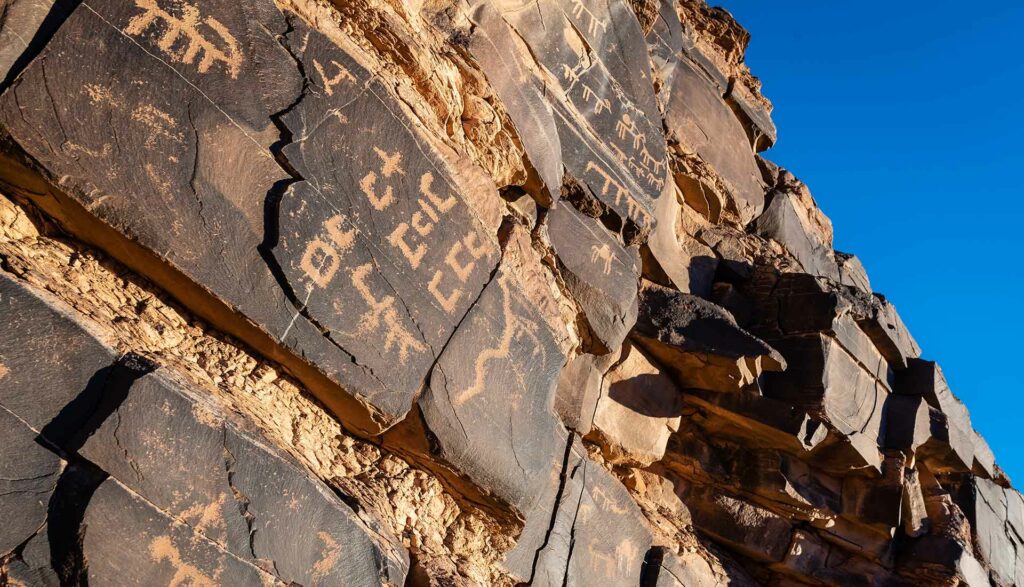

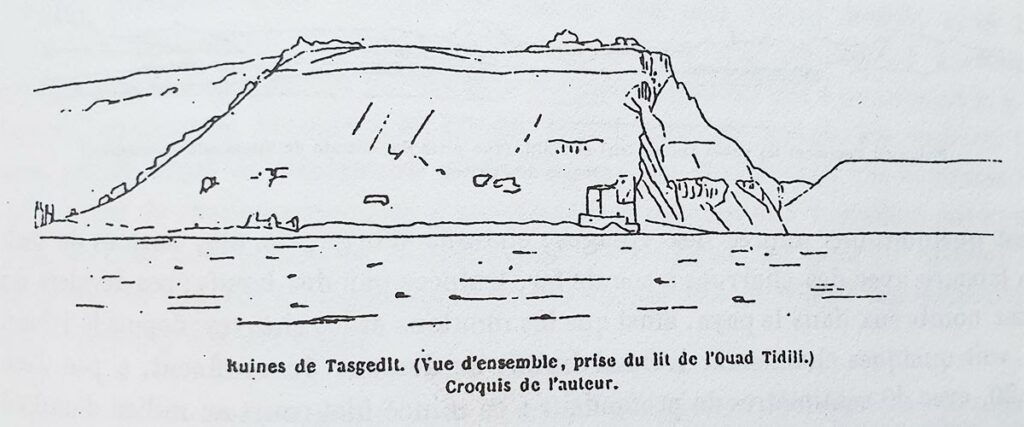

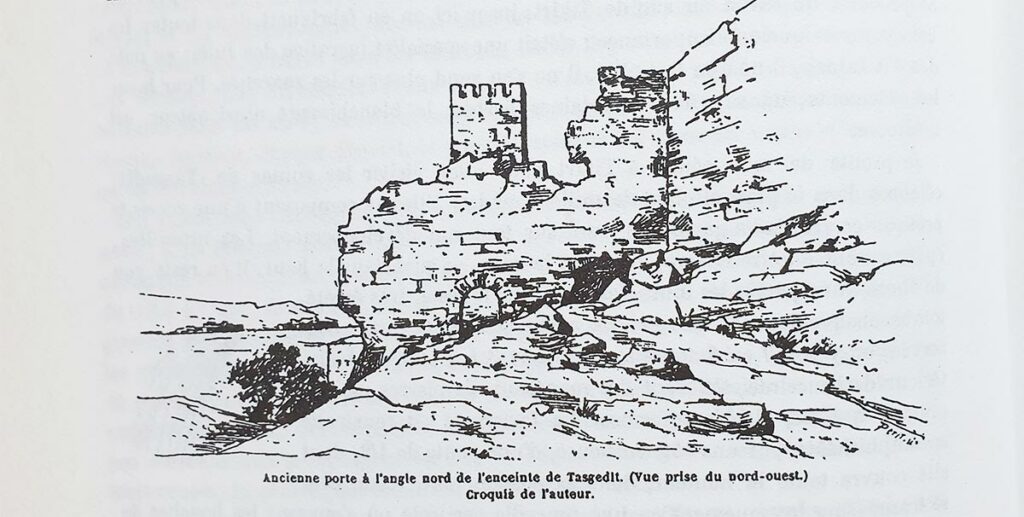

He takes advantage of this stay in Tikirt, where he resides for a week, to get a closer look at the ruins of an ancient citadel, in a place called Tasgedlt located a few kilometres away, and around which, in his own words, “a thousand-year-old legend is woven”. The account he writes in his notebook makes it easy to imagine how the story could have been related to him, in such a way as to arouse the curiosity of any witness:

« In the past, many centuries ago, three princesses, daughters of a Christian king, reigned over these regions: one, named Doula bent Ouâd, resided in this fortress of Tasgedlt; another, Zelfa bent Ouâd, lived in a similar one, on the banks of the Marren river, near Teççaïout; the third, Stouka bent Ouâd, again similar to Taskoukt, on the Imini river: in all three of these places, we can observe similar ruins. »

Charles de Foucauld – Recognition in Morocco – 1883

Having walked the few kilometres up to the village of Tasgedlt, he observes, from afar, the remains of what can be assumed to be a fortress, distinguishable through its towers, and that stretches all along the sides of a hill. The place is scattered with other ruins of further buildings.

He takes the time to sketch the whole, as well as the most prominent part in the shape of a wide front door. Even today, what remains of the building, and the imposing width of the surrounding walls, suggests the importance of the place and gives credence to the idea that this place must have indeed once been the residence of someone of great nobility.

In search of the lost princesses

Charles de Foucauld admits, however, to having little faith in the reality of this beautiful legend. He explains that the account given to him by the villagers of Tikirt establishes that the arrival of Muslim armies from the 7th century onwards brought about the downfall of this Christian monarchy and caused the precipitous departure of the princesses. He also opines that the ruins must have been the remains of old kasbahs built by any one of the sultans. Each of these three places where, according to the legend, the sisters are said to have settled, bear similarities to each other.

However, his conclusion contradicts his own observation that these large territories have always been beyond the control of any sultan. Above all, it clashes with the amplitude of this legend which has carried the tale of these princesses for centuries, and which is based on other factual observations that the explorer strangely did not make in his time.

It is in fact within the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou, located a few kilometres from the Tasgedlt’ ruins, that, in the maze of narrow streets, there is a disturbing element that reinforces the glow of this legend. An oral tradition in this village indeed reports that a very old well, located between the two surrounding walls that once protected the village and its granary, bears the name of Anou n’Tarmouyte; in other words the Christian’s well.

Better yet, when divulging a little more about this strange name, the elders of the ksar community enjoy telling their own version of the story. According to them, King Ouâd would have indeed existed in very distant times, but he had had four daughters, not three. This fourth, named Aïssatou, had taken over power upon the death of her father and is said to have settled precisely in that place known today as the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou.

So, they say, it was she who had the well dug, and indeed, when the Muslim troops arrived, she would have been forced to flee to escape the warrior attacks and would have left the village through its north gate in order to head towards Telouet, in the hope of reaching the other side of the Atlas Mountains.

Today, a ruined tower overhangs this old well. But in the past, this tower was part of the northern gate of the ksar through which Princess Aïssatou ran away, and this ruin is nowadays known as L’Borj n’Tarmouyte, which means the Christian’s tower.

Morocco, a place of an intermingling of confessions and traditions

Located on the banks of the Ounila river, the fortified village, igherm in the Amazigh language, Aït Ben Haddou, has been world famous ever since its UNESCO classification as a world heritage site in 1987. Its singular silhouette stands as the symbol of Amazigh architecture in Morocco, and ultimately of Morocco as a whole. The village of Aït Ben Haddou was once a staging point for the large camel caravans of the trans-Saharan trade, but, nevertheless, Charles de Foucauld and his guide passed by without stopping. The explorer thus missed out on the story of Aïssatou, the fourth Christian princess.

The legend and its narrative which still linger in the memories of the elders remind us that in Morocco, before the 7th century and the arrival of the first troops of General Oqba Ibn Nafi al-Fihri from the Arabian Peninsula, the Amazigh population, the native population of these territories, had, over a period of nearly a thousand years, already welcomed many communities from the East bearing Phoenician, Jewish, Roman or Christian culture.

And what about these intermingling populations that have blended all these faiths and traditions? How far could this learned mixture have extended? On what fertile or even arid lands was it able to flourish as a community, principality or kingdom?

The homelessness of the oppressed as the primary vehicle for spreading the faith

The last words uttered by Jesus of Nazareth, as reported in the Gospel according to St. Mark, might suggest that the expansion of Christianity is, above all, based on ideological voluntarism:

Then he said to them, « Go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation »

Mark 14.15

Reality, as so often, is more complex. After his death, the disciples and faithful followers of Jesus, commonly called the Galileans, constitute just one more group among an undoubtedly dominant but later fragmented Judaism, which found itself in a crisis as to its meaning. However, during the initial process of Christianization, their migration very quickly began following their expulsion from Jerusalem in the 35s A.D after the lynching of one of these Jews’ first charismatic figures. This was, the so-called Stephen, who has since been regarded as the first of the Christian martyrs.

These first exiles will quickly settle in nearby regions, such as Antioch or Cyprus, Phoenicia or Damascus, to constitute the first centres of what would slowly become a new religion.

In the year 70 AD, the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Roman armies under Nero’s leadership sets in motion a long-lasting dynamic scattering of the Jewish people, mixing all faiths.

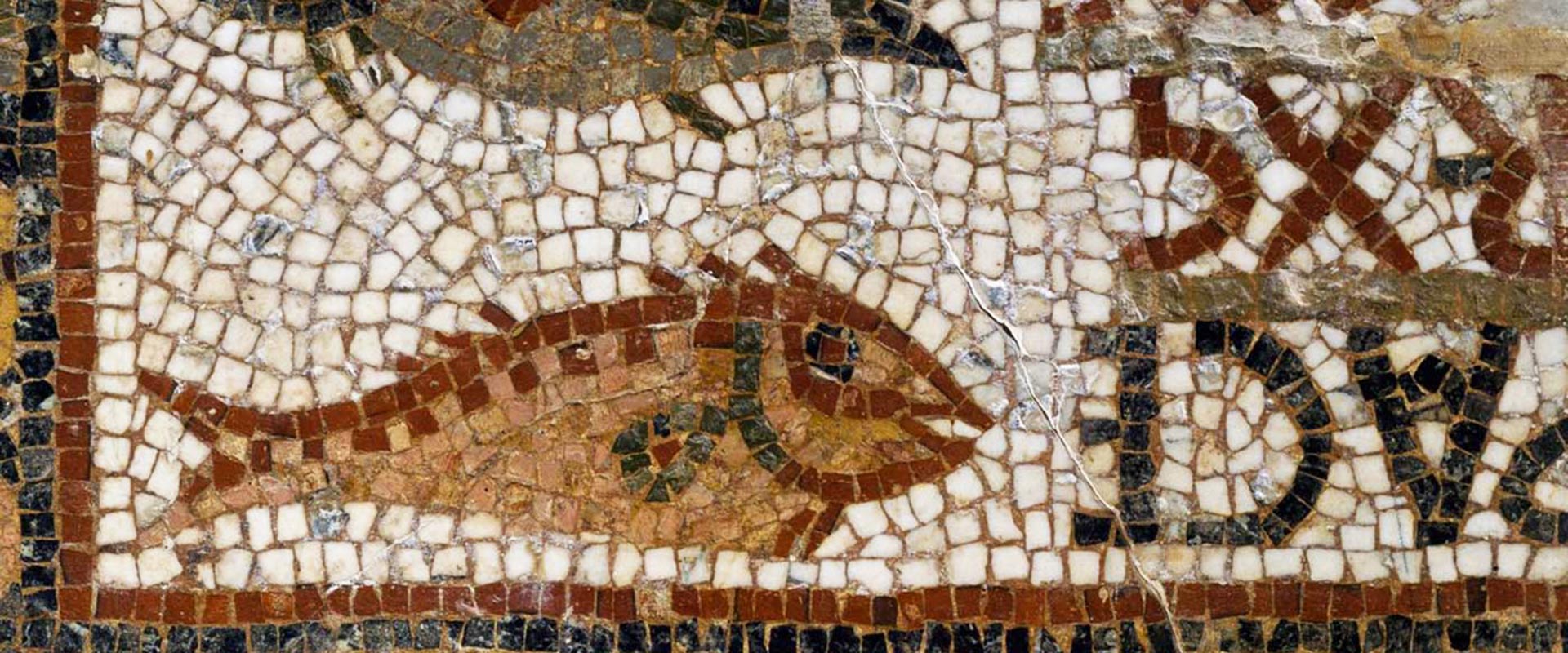

El-Jem Archaeological Museum, Tunisia

The emergence of African Christianity

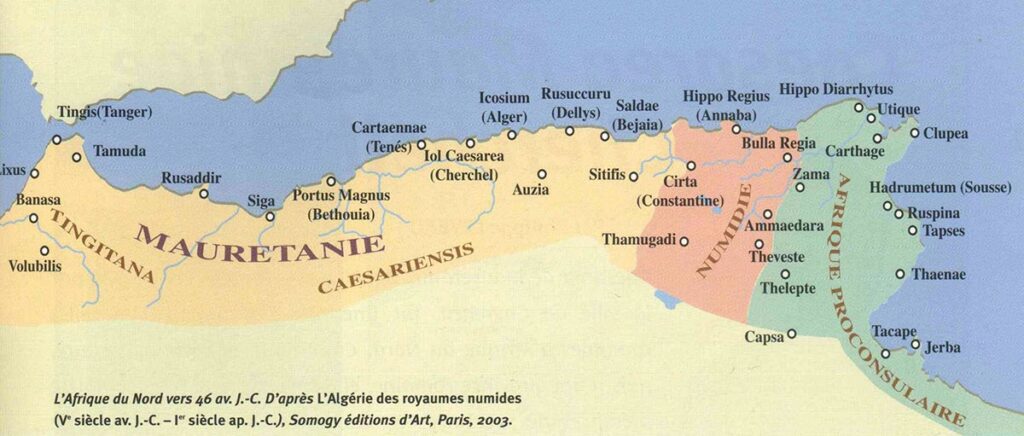

These exiled populations arriving in the territories of North West Africa is self-evident, particularly because of the attraction of Carthage, today’s Tunisia, a city under Roman occupation since its destruction in 146 BC., and where a large Jewish community had already been living. As history tells us, twelve Christians, as the martyrs of Scilli, were executed in Carthage during the year 180 by order of the proconsul of Africa. Barely fifty years later, a Christian community will be consolidated to the point where, in the 240s AD, the bishop of Carthage, their leader, could establish a council bringing together nearly a hundred other bishops from the surrounding Christian communities.

Bishop : The word comes from the Greek Eπίσκοπος / episkopos which literally means “supervisor”, that is to say moderator, responsible for a community. Source: Wikipedia

Carthage will thus become a focal point of Christianity in Africa from which emerge important personalities, all of them Berbers converted to the new Christian faith, such as Tertullian, Cyprian or Augustine of Hippo, who will go down in history as Saint Augustine.

At the end of the 2nd century, the writer and philosopher Tertullian testifies in one of his books that the expansion of Christians was energetic. He addresses the Roman authorities as follows:

« We are but of yesterday and we fill everything, your cities, your islands, your castles, your decuries, your palaces, your senate, your public places … »

Tertullian / Apologetics – Source: History of Morocco / François Decret

Christianity is thus known for having first established itself in the already Romanized cities of the former Berber kingdom of Mauretania, better known as the Moorish Kingdom, under various sovereigns such as Bocchus, Juba II or Ptolemy. This was the case in Tangier (Tingis) or in Volubilis, in Asilah (Zilis), Ceuta (Septem), Larache (Lixus), Tétouan (Tamuden-sis) or Salé (Salensis).

But it was still under the threat of violence that the dispersal of the new believers increased and caused some of them to leave risk areas such as large cities in order to take refuge further inland, to be exact beyond the High Atlas Mountains. The fierce persecution of African Christians at the beginning of the 4th century, under the authority of the Roman emperor Diocletian, must thus have caused innumerable exoduses.

Fresco, Lateran Palace, Rome

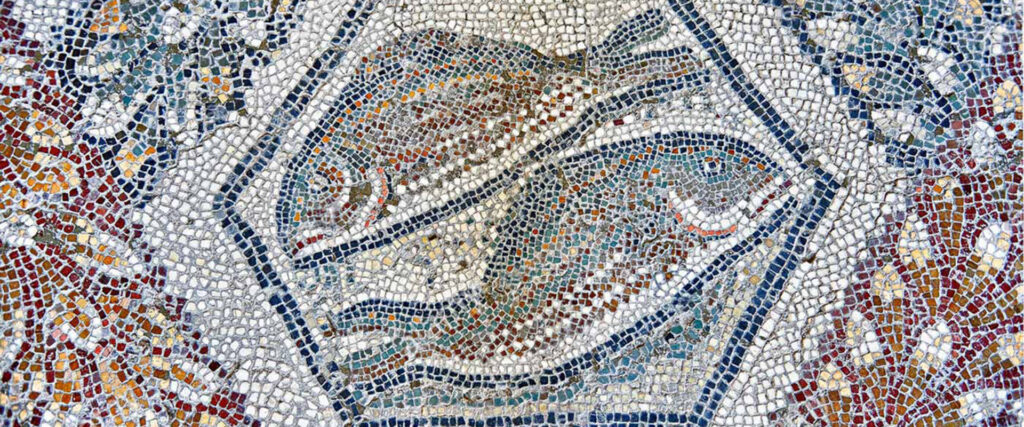

Mosaics of Saint Sophia, Constantinople

The Amazigh kingdoms as a place of refuge for Christianity

It will take until the conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine in the year 313 that a lull could allow the new religion to expand more tranquilly over the following decades. But this last period of persecution by the power of Rome also resulted in the emergence of a divergent ideological current within fledgling Christendom, which reached a significant following among the poorest and least educated communities, principally in vast rural areas.

This current, called Donatism, was opposed to the new alliance that was being established between Christianity and the Roman Empire. Its followers and thinkers sought to define a vision of faith more anchored in what they call the Holy Spirit, that is, the flow of the spirit of God among humans. This current will end up being considered as heretical and will be strongly opposed. But by then, it will have diffused a vision of the Christian religion strongly linked to the worship of the saints and the martyrs. This is not to forget the ease with which the Amazigh tribes welcomed Sufism a few centuries later and, in rural Morocco, allowed the establishment of a popular tradition dedicated to the glory of the saints illustrated by the emergence and the increase of the zaouias.

Zaouïa : is a Muslim religious building which constitutes the center around which a Sufi brotherhood is structured. By extension, it often refers to the brotherhood itself. Source: Wikipedia

The scenario of chaos resumed with the invasion of the Vandals from Europe in 430. This period of great violence lasted almost a century and saw the emergence of another version of Christianity, called Arianism, which once again brought about a new cycle of persecution, confiscation of property, destruction of places of worship and forced conversion. Again and again, the consequence of this was a new exodus for Christians loyal to their original faith. Once again this exodus was into the interior territories of the country, where various Berber kingdoms and principalities had emerged fiercely resistant to all successive invaders.

All these excluded and persecuted peoples had to find benevolent havens of peace in these Amazigh territories. The heads of these kingdoms, often Christian, carried Roman titles for a long time, as did the sovereign Masuna within the Kingdom of the Moors and the Romans, and who was designated as the Rex gentium Maurorum and Romanorum.

At the end of the 5th century, the kingdom of Altava took over from the Kingdom of the Moors and Romans and brought to life a Christian Berber culture in the territories of the former province of Mauretania Caesarean. Today this corresponds central and western Algeria and part of north-eastern Morocco.

The melodiousness of their existence resonates until today

The establishment and influence of Christianity in North Africa is therefore a reality throughout the first centuries of the first millennium. It is more than likely that its spread was beyond urban sites towards interior territories where the powers of the moment didn’t wield any authority. The confessional confrontation with the paganism widespread among the indigenous Amazigh populations must certainly have created friction, but important theological or religious bridges must also have facilitated conversions to Christianity.

We also know that the arrival of Islam to the shores of the Atlantic coast in the 7th century did not result in the immediate disappearance of the presence of Christianity. The complete erasure will take place five centuries later under the authority of the Almohad dynasties, at the same time as the disappearance of other currents, such as Shiism and Kharijism, throughout the Maghreb.

Despite the absence of historical sources that can attest to this today, it is therefore more than likely that the territories of south-eastern Morocco were able to welcome a Christian kingdom.

The existence of Doula, Zelfa, Stouka and Aïssatou, the four princesses’ daughters of the King of Ouâd, is therefore just as probable, as is their reign over the lands today united and named the rural Moroccan commune of Aït Zineb.

The persistence of their memory today among the inhabitants of the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou, just as at the time of the explorer Charles de Foucault, reinforces the possibility of this reality and mainly because the melody of their first names still resonates in the name of the places that once hosted them.

Where Doula Bent Ouâd had settled, in the fortress of Tasgedlt visited by Charles de Foucauld, the douar today bears the name of Tadoula, the prefix “Ta” indicating the feminine form of a name in the Amazigh language. Today, the douar where Stouka Bent Ouâd is supposed to have been living is named Taskoukt.

And the Ksar of Aït Ben Haddou, which once was the home of Princess Aïssatou, has for centuries been named after its official founders, the Aït Aïssa family.

A final clue sheds light on the legend in a most masterly fashion, so as to validate it forever: Aïssa is the Arabic translation of the name of Jesus.

Version française : Il était une fois au Sud Est du Maroc, quatre princesses chrétiennes …