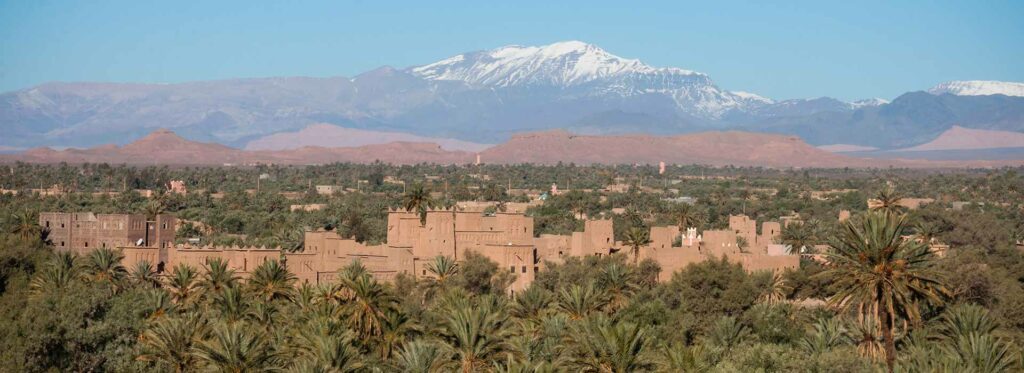

One eventful day, the village of Tazouda, located a few kilometres from Ouarzazate in the foothills of the High Atlas Mountains, saw the bones of what was later construed to be the skeleton of the oldest dinosaur ever discovered in Morocco emerge from its dusky soil. The news of this discovery in 1998 and the results of excavation work undertaken between 2001 and 2007 had such an impact on the population that everyone’s imagination – adults and children alike – began to sketch out a future consistent with this mysterious animal’s existence, which, thanks to Hollywood stories, even taken on features of a quasi-character.

The dinosaur from Tazouda is in fact the emissary of numerous potentialities. First and foremost, it is a tremendous lever for the development of both the village and the surrounding area, thanks to its obvious tourist appeal, thus supporting bookings at guest houses and hotels. But it also has the capacity of being a source of knowledge for scientists concerning the history of our Earth, as well as providing schools with a teaching aid. Finally, this dinosaur reinforces Moroccan pride in their heritage.

Dinosaur: the word is derived from two Greek roots – δεινός deinos, meaning terrible and σαύρα sauros, that is to say reptile or lizard.

We knew the region was rich in fossils, we knew of the drawings engraved on rocks by ancient hands, but we did not suspect that the South East, the natural treasure of Morocco with its valleys, its mountains, its oases and its deserts, had also sheltered the hero of the remotest of times, the emblematic figure of those vast epochs before humans ever inhabited the Earth. And yet, nearly 180 million years ago, here in Tazouda, dinosaurs breathed their last on the sandy bed of a loop in the river. Their bodies disappeared and their bones slowly became covered with sediment.

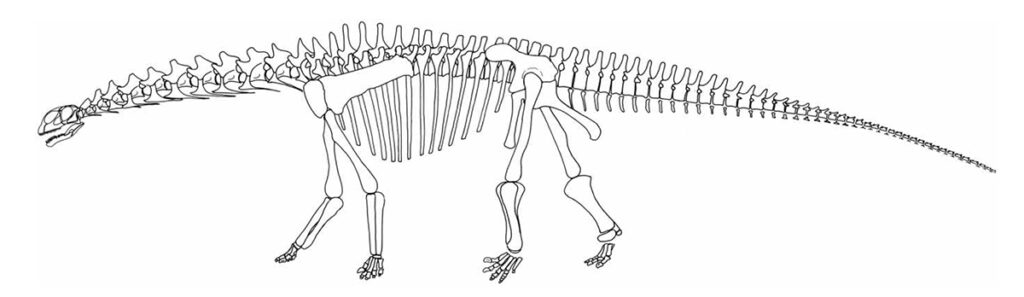

Long afterwards, what remains of them has allowed a reconstruction of the aptly-named Tazoudasaurus naimi.

Morocco at the crossroads of drifting continents

In those distant days, the dinosaurs that populated the lands of what was to become Morocco had nothing to complain about concerning their natural environment. The climate was favourable to them, tropical in nature, i.e. warm and humid. The rocky plateaus of today were covered with lush vegetation, and numerous rivers and streams. The dinosaurs fed on the leaves of trees, such as the Araucaria or the largish cypresses, and on giant ferns.

The Atlas Mountains had not yet been formed. We are in the heart of the geological era known as the Mesozoic, which lasted from 250 to 65 million years ago, a grand period in our history sometimes referred to as the “Middle Life Era”.

The Mesozoic (from the ancient Greek mesos: μέσο, middle and zoon: ζῷον, animal), formerly known as the Middle Era (or Reptile Era), is a geological era in which species of mammals and dinosaurs appear.

Imagine Morocco at the beginning of this Middle Era. All the landmasses had fused together over the previous 200 million years to form a single block, an immense continental mass that we now call Pangea, surrounded by a single ocean.

Morocco finds itself isolated right in the centre of this mass. The climate is dry and arid. Further south, the territories had just been through an ice age of over some 20 million years. The oscillations between temperatures were extreme. And for obscure reasons, following the dictates of some invisible clock, this lonely continent slowly begins to dislodge itself. It will twist in the middle, almost splitting into two, and then later into five pieces. The waters of the surrounding ocean penetrate the rocky masses, a marine corridor is formed and from one erosion to the next, from east to west, from what will become Arabia to the lands now forming Central America, a new sea is formed, the Tethys, which, by the narrowing of its two extremities, will later become the Mediterranean Sea.

Morocco, once lost in the middle of the desert, is once again at the mercy of the waves, and sees its climate change.

The name Pangaea which literally means “all lands”, comes from the ancient Greek πᾶν (pân), “all”, and γαῖα (gaïa), “earth”, which in Latin becomes pangaea.

Morocco, the cradle of all life on Earth

The presence of these large reptiles in Morocco has long been confirmed, by virtue of numerous discoveries, such as that of the first terrestrial vertebrates, amphibians, other more ancient reptiles and the first mammals. Scientists know that Morocco, thanks to its geographic location, is the cradle for all life on Earth.

The bones of the first large sauropod dinosaur were found in 1925 near El Mers, in the eastern Middle Atlas. In 1934, impressive footprints were discovered by French scientists at the Aït Iouaridene site. Between Demnate and Aït Bou Guemez, in the High Atlas, long tracks of footprints have been found, some measuring 115 cm in length and 75 cm in width. These belonged to herbivorous quadrupedal dinosaurs, with other tracks from bipedal and carnivorous dinosaurs which, although smaller, were nevertheless impressive because of their three imposing fingers. These footprints, solidified in the limestone soil once covered in water, attest to an abundance in Morocco, particularly in the regions that would later form the Atlas Mountains.

Michel Monbaron is an expert on the subject and his scientific career is linked to the presence of dinosaurs in Morocco. A Swiss geologist, he has been surveying the steep slopes of the High Atlas since 1976.

In July 1979, near Tilougguit, he was the one who discovered the first bones of the Atlas Giant, a massive dinosaur measuring more than 18 metres in length and 6 metres in height, including 3.5 metres of front and rear limbs. The interest of this discovery lies in the fact that the skeleton is almost complete, with the exception of the tip of the tail. And a rare occurrence is the presence of the animal’s skull bones, which are very fragile and often absent from such excavations. This specimen was named Atlasaurus Imelakei, and to this day represents the largest dinosaur that has ever been discovered, and is the only one found so intact in Morocco.

A few years later, alongside Najat Aquesbi, then head of the Geology Museum at the Moroccan Ministry of Energy and Mines, Professor Philippe Taquet of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris (MNHN), Dale Russell of the Center for the Exploration of the Dinosaurian World (USA) and Ronan Allain, a researcher at the MNHN, Michel Monbaron participated in unearthing the bones at Tazouda village with the intention of dating them as precisely as possible by studying their geological environment. Vegetable debris, consisting of the remains of ferns, cycads and conifers, were also discovered alongside the bones.

It was Michel Monbaron who confirmed the time markers of between 190 and 175 million years ago, i.e. the end of the Lower Jurassic, and thus assigning to one of the remains – an almost complete jaw – the proud attribute of being the oldest fragment of a sauropod skull currently known in the world.

A discovery with global scientific repercussions

From 2001 to 2007, the excavations undertaken under the direction of Ronan Allain confirmed the importance of the Tazouda site, since nearly 600 dinosaur bones in a very good state of preservation were recorded, including parts of a skull and its mandible bearing 17 teeth. Two dinosaurs were identified, a sauropod herbivore of unknown type named Tazoudasaurus naimi (the bones represent at least ten individuals ranging from juveniles to adults) and a bipedal carnivorous theropod, also of unknown type, which will become known as Berberosaurus liasicus.

Tazoudasaurus Naimi: this name is derived from the name of the locality where it was found, Tazouda, and from sauros, which means lizard in Greek. The word naimi comes from the Arabic word for slender, and refers to the small size of this type of dinosaur.

The uniqueness of this discovery lies in the fact that continental deposits from this period, the Lower Jurassic (between 199 and 176 million years ago), are only found in just a few places on Earth. As a result, very little is known about the history of dinosaurs in this period. The scientific implications of the Tazouda discovery are therefore world-reaching.

Souce: Peyer, Karin and Allain, Ronan (2010) ‘A reconstruction of Tazoudasaurus naimi (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco’.

Michel Monbaron explains:

« The location and the richness of the Tazouda deposit amply justify the construction of a museum at the exact site of the discoveries, and which thereby opens up unique possibilities … The visitor has access to the fossiliferous slab where he can admire the scapulae, the femurs, the vertebrae in the very place they were found … »

This kind of museum with public exhibits at the site of the discoveries is very rare and the one in Tazouda will be the first in Morocco. The building construction so far has been thanks to a large financial donation from two French patrons, Danièle and Armand de Ricqlès. An association has been created to ensure the follow-up of the project. A scientific committee has also been established but the interior of the museum has not yet been completed.

Moussa Masrour, coordinator of the scientific committee of the Tazouda museum, explains that future visitors to the museum will be invited to follow a discovery trail, starting from the site of the excavations with a reconstitution of the discoveries in the form of bone casts. A life-size reproduction of the Tazoudasaurus is envisaged. There will be display cases showing fossils, plus information panels explaining the evolution of species and the habitat of dinosaurs.

Once finished, the Tazouda museum will complement the future Azilal museum, on the other side of the Atlas Mountains, which will present the imposing skeleton of Atlasaurus Imelakei to the public. The opening of the Azilal museum is planned for 2020 and it will be the focal point of the M’Goun Geopark, a vast territory being promoted under the innovative label of “Global Geopark”, a label validated by UNESCO in 2014. The intention is to offer the public a unique presentation of all the mineral, fossil and natural treasures of this region so rich in history.

Linked in this way, the two museums devoted to the dinosaurs of Morocco will shed light on what was once the life trajectory of these great reptiles that disappeared 65 million years ago, at a time when the Atlas Mountains had not yet been formed, and the plains were frequently covered with water and home to an abundant fauna and flora.

The region of south-east Morocco is indeed full of traces of our planet’s great past and, for international palaeontology, prevails as an important reservoir of discoveries. Moussa Masrour cites the Fezouata area in the vicinity of Zagora, where the remains of an exceptional Ordovician fauna can be observed, also with world scale referencing, or the Kem Kem site, which contains a wide variety of fossils such as those of dinosaurs, spinosaurs, crocodiles and turtles, or the Agdz region with its stromatolites.

The urgent need to make this cultural jewel shine on Tazouda

The completion of the museum in honour of the Tazoudasaurus naimi has been postponed several times, once from 2011 and again from 2015, and since then no clear date has been revealed. But the future seems full of promise: the person in charge of the project, Mr. Lhouceine Maaouni, Provincial Director of Energy and Mines in Ouarzazate and the new President of the Tazouda Association, confirmed that, despite the series of delays, the project has been resurrected, notably at the impetus of the Governor of Ouarzazate Province, Mr. Abderzak El Manssouri, a fervent supporter of plans to construct museums.

It is to be hoped that those in charge of the Drâa Tafilalet Regional Council will finally open their eyes to the riches that Nature, and thereby Providence, has offered to the region they are responsible for, and that they will follow the example of their counterparts in the Béni Mellal-Khénifra region, who have shown vision and admirable accomplishments in setting up the M’Goun Geopark; a tremendous driving force for the development and growth of the country.

Everything is in place for the opening of this cultural jewel to the public, waiting to shine on the territory of Tazouda village, to the benefit of its population who have great hopes, and rightly so, for what will become the flagship tourist attraction in the province of Ouarzazate as well as being the pride of the Drâa Tafilalet region, and of the whole of Morocco.

The day will come when the dinosaur of Tazouda truly will emerge from its slumber and receive the honours it deserves.

One Response

Congratulations on this new and beautifully researched article that reminds us of the richness of our exceptional heritage – geological, fossil, natural, historical, and human – in the Southeast of Morocco, and for awakening Tazoudasaurus Naimi from its slumber.