For over two millennia, a thriving Jewish community flourished in southeastern Morocco, weaving deep connections with the local populations. Settled in oases, ksour, and medinas, they played a pivotal role in the region’s craftsmanship, trade, and cultural life. Once an integral part of the social fabric, their presence gradually faded, leaving behind abandoned synagogues, deserted mellahs, and stories scattered between memory and oblivion.

The reasons for their departure are manifold: political shifts, economic upheavals, and new aspirations led to a mass exodus to Israel, Europe, and North America. Yet, despite the distance, this diaspora maintains an unbreakable bond with its homeland, where echoes of its past still linger. Rediscovering their history unveils a lesser-known facet of Morocco’s heritage and sheds light on how this legacy continues to shape the identity of the country’s southeastern region.

And after the Phoenicians, will come the Romans, the Byzantines, the Ottomans, the Arabs … For centuries, the countries of North West Africa will become a crossroad of multiple passions and ambitions, an Eldorado for all dreamers, the crucible of a continuous mixing of cultures, and the place where a country is slowly and laboriously being forged, Morocco.

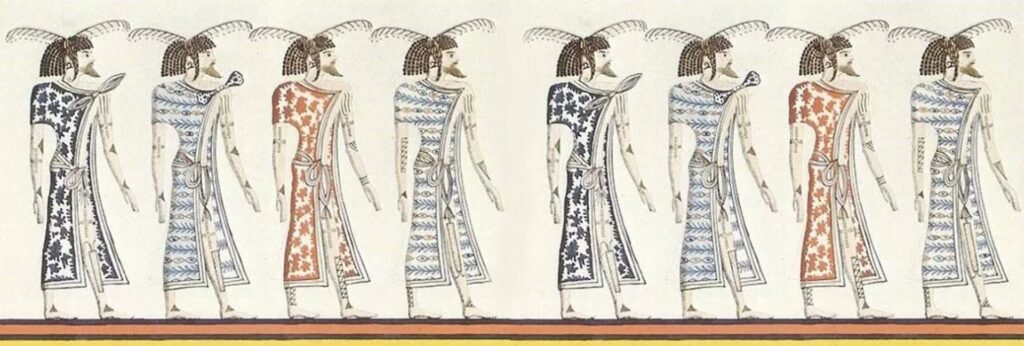

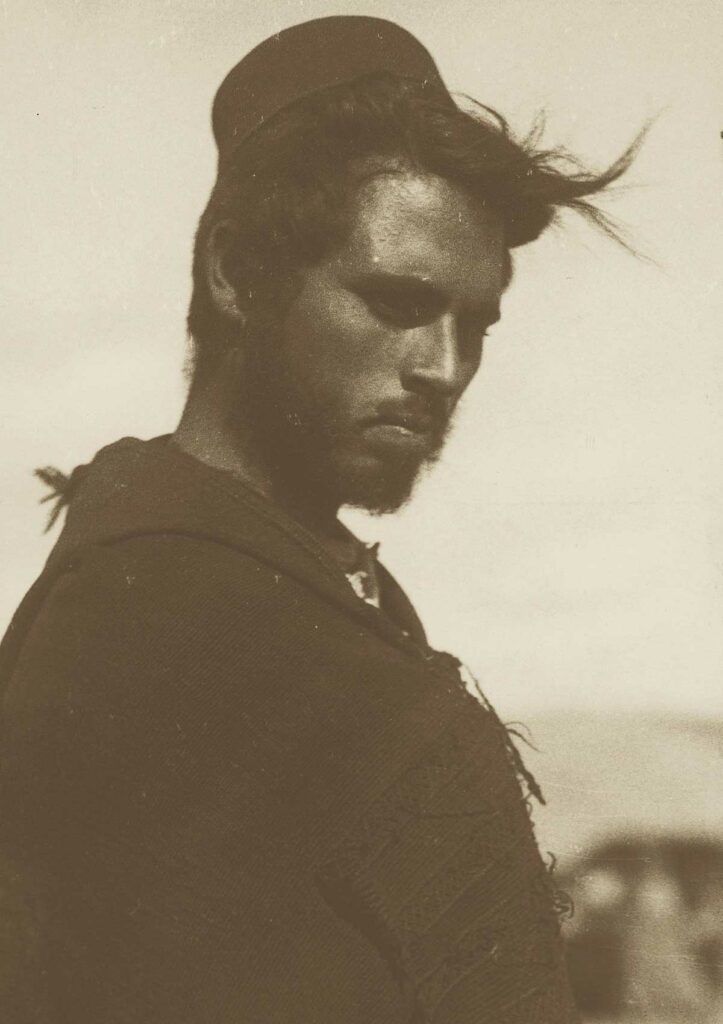

Very early and scattered within these migratory waves, Jewish communities settled here and then across the region frequently on the run from far-away places and with no other purpose than to find some land to build an existence. They participated in the life of their host territories, combining hand, heart and intelligence with the labours of other communities already there, or with those who would join them later, thus all weaving together, generation after generation, the pluralistic identity of what would later become Morocco.

The formation of a mosaic people

The first waves of Jewish immigrant communities probably arrived on board Phoenician ships along the Atlantic coast near the mouth of the Oued (River) Noun, close to Guelmim in southern Morocco. Different groups would have gradually moved further inland, in particular towards the Drâa and Dades valleys, Tafilalet and the High Atlas. Legend has it that King Solomon sent Jewish explorers to the Drâa region to look for gold around the 10th century BC. Some groups would have reached South East Morocco directly from the interior of the continent after the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BC and following the deportation of surviving Jews to Babylon.

Historically, concrete evidence of their presence in Morocco dates back only to the 2nd century BC. This is from funerary objects found in the Roman ruins of Volubilis with inscriptions in Hebrew and Greek.

Until the arrival of Arab tribes in the 7th century, more than thousand years passed enabling Jewish, Berber and sub-Saharan communities to shape a coherent social and cultural whole. Judaism, Christianity and paganism, as belief systems, were thus able to express themselves either in conflict or in harmony depending on the period and on the current ruling power, local powers or foreign and occupying powers, such as the Romans, the Vandals and the Byzantines.

The ever-increasing influence of Islam obviously changed the situation. Above all, Jewish communities had always been protected from great Roman or Byzantine persecutions by being placed under the status of Dhimmi. This social position, in fact, discriminatory, nevertheless ensured their security and could even be granted greater flexibility, depending on the frame of mind of successive sultans or local chiefs.

Even though the Jews are plunged back into a period of persecution under the Almohad Caliphate, subsequent sultanates will permit the emergence of symbiosis between the Jewish, Arab and Berber communities. This harmony was felt most strongly in rural areas, where human groups formed one single community. Each of the communities preserved their cultural identity, but over the years, many of these cultures were intermarried, thereby slowly being reshaped.

The German historian, Shlomo D. Goitein, was able to observe :

« Judaism has never been in such a strong relational environment and fruitful symbiosis as with the medieval civilization of Arab Islam. »

In Morocco, the communities unwittingly forged a common destiny, as much due to an accumulation of common past as through the tragic upheavals of both history and life.

In the 17th century, after they were expelled from Andalusia, all three communities, Berber, Arab and Jewish, took refuge in Morocco. This event will doubtless have aroused a common nostalgia for the Iberian El Dorado, stimulating a mutual enrichment of their individual cultures.

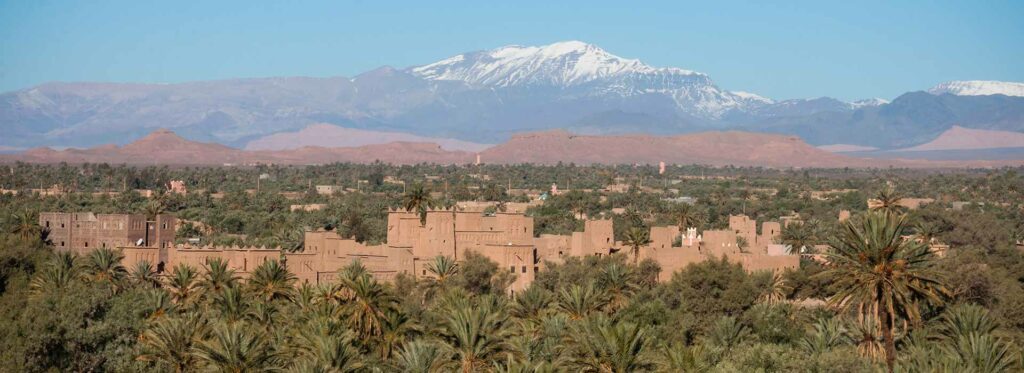

The Drâa valley, a cradle of settlement and cultural influence

South East Morocco, due to its geographical location, was one of the territories privileged to support the settlement of Jewish communities. Their presence is of such significance that the only documentary sources about of the region’s history prior to the arrival of Arab tribes are Hebrew manuscripts, dating from the 12th century. These documents report the arrival of nomadic Jews by camel caravan around the 5th century BC and their settlement in a place called Taourirt N’Tidri, which means Hill of Tidri, near present-day Zagora. Stone and earth remains can still be seen nowadays and testify to the ancient presence of the Jews.

From Tidri, the Jews scattered all over the surrounding territories such as Beni Sbih and Beni Hayyoun, Amzrou south of Zagora, Asselim N’Ougdz, Tamnougalte, Tazroute, Tagmadarte, Mhamid El-Ghizlane …

In these same mythological tales, mention is made of the city of Tamegroute, founded by Jews as the capital of a Jewish kingdom of Drâa which would have dominated the neighbouring area from the 7th century until the end of the 11th century when Muslim Berber tribes, the Sanhadjas, arrived. These tribes were known to have established the Almoravid sultanates who plunged the Jewish communities back into a new cycle of persecution, removing them forever from any possibility of exercising authority over their places of habitation.

Tamgroute was renowned for its urban character but mainly for its cultural influence where Hebrew science enjoyed great fame throughout southern Morocco. Talmudist scholar Moïse Abraham Halevy Ed-Draoui is an emblematic figure of this period around the 10th century.

Source : www.ouarzazate-1928-1956.fr

The Dades Valley, the Ziz valley, and all over that of Tafilalet …

The Dades Valley has accommodated important Jewish settlements such as the site of Tiylite, located a few kilometres from present-day Kelaa M’Gouna.

A 12th-century book, titled Kitâb Al Istibṣar and written by an anonymous Arab geographer mentions Tiylite under the term Madina, which means city, as a staging point of trans-Saharan caravans, protected by a fortress and garrisons, headed by a Wali, namely the governor. Tiylite was indeed a focal point for the surrounding population as shown by the list of families buried in its Jewish cemetery: Ait Ouzzine, Ait Tazarine, Ait Ofilal, Imeghrane, Ait Hnana, Ait Icho, Ait Messoud, Ait David …

The Todgha and Dades Valley welcomed large Jewish communities coming from Al-Andalus, the former Islamic states in Iberian Peninsula, after the Reconquista by Christian military forces. The ksar of Asfalou was thus an important place of residence for the Jews of Todgha such as the Ksar of Tinghir, Taourirte and Ait Ourjdal. The social importance of Jews in Todgha is explicitly expressed in a local Amazigh popular song :

In Tinghir D’Taourirte D’Asfalou, Oudayn Akent Igan D ’Teqbiline

O Tinghir, Taourirte and Asfalou, it is the Jews who have enabled you to become tribes.

In the Tafilalet region and around the Ziz basin, many Jewish communities grew and flourished. Some of them experienced great economic and social development within the famous city of Sijilmassa founded by the Berbers Zeneta in 757 BC. After the decline of this radiant city in the 14th century, the Jews took up residence in other places such as the ksar of Tabouâssamte, that of Almamoun or Alfouqani as well as in the ksar of Beni Moussa or Moucheqlal.

Tafilalet is also the birthplace of great Jewish rabbis such as Rabbi Ya’akov Abehssera born in 1889 in Rissani, Rabbi Moul Tria and Rabbi Moul Sedra.

Names of Jewish families still resonate in collective memories such as Benchetrit, Benitah, Bensemhoun, Dahan, Illouz, Mamane, Nezri, Teboul Hazout, Bensaid, Zenou, Amoyal … as well the Benhamou family and the Azeroual one in Boudnib close to Errachidia.

Once the organization of Jewish urban areas, namely the Mellahs, had become the norm in the largest Morocco’s cities in the 19th century, towns and villages in south-eastern Morocco also set up areas dedicated to Jewish communities, and some of them achieved great fame such as those of Rissani, Erfoud or Demnate.

A mellah (Arabic: ملاح, romanized: Mallāḥ, lit. ’salt’ or ‘saline area’; and Hebrew: מלאח) is the place of residence historically assigned to Jewish communities in Morocco / Source : Wikipedia

Ouarzazate also hosted large Jewish populations, particularly in the villages of Telmasla, in the Casbah of Taourirte, in Tamassinte, Imini or Tikirt. Rabbi Yihia Ben Baroukh Cohen Azogh rests in Tifoultoute. In Agouim is the tomb of Rabbi David Ou Moshe, born in Jerusalem. Furthermore, the village of Tazenakhte was above all renowned for the presence of an important theological document called Sefer Tislit or the Scroll of Tislit, in its synagogue.

A symbiosis between Jewish and Muslim communities

Jews and Muslims therefore shared a common existence and, equally, they built a common destiny. Such a fusion gave rise to a mixed culture, Judeo-Berber-Arab, where many components of their identity were shared, like the worship of saints and ritual ceremonies around their tombs. These are the Moussem on the Muslim side or the Hiloula on the Jewish side. The two communities very often venerated the same saints, but under different names. In the Drâa region, Jews and Muslims used to celebrate the same saint, named Isaac Akkouim by the Jews and Sidi Moussa by the Muslims, through a pilgrimage to his tomb in Tidri. In Demnate, another saint named Haroun Ben Cohen was also revered by local Muslims as Bou Lbarakat, which means One who bestows blessings.

Moussem : local festivity that combines a religious celebration to honor a saint with festive and commercial activities. Hiloula : the first meaning is “to cry out with joy and fear” and describes a Jewish custom of going to the tombs of the Tzaddikim (the Righteous) on the anniversary of their death to commemorate them through a festive ceremony.(Source : Wikipedia)

This cultural harmony between Jews and Muslims is also reflected in peoples’ surnames. Few of Moroccan Jewish families names are linked to a Hebrew or Aramaic etymology. The majority of them are Berber, Arabic, or sub-Saharan, expressing professional activity, tribal lineage or geographical origin.

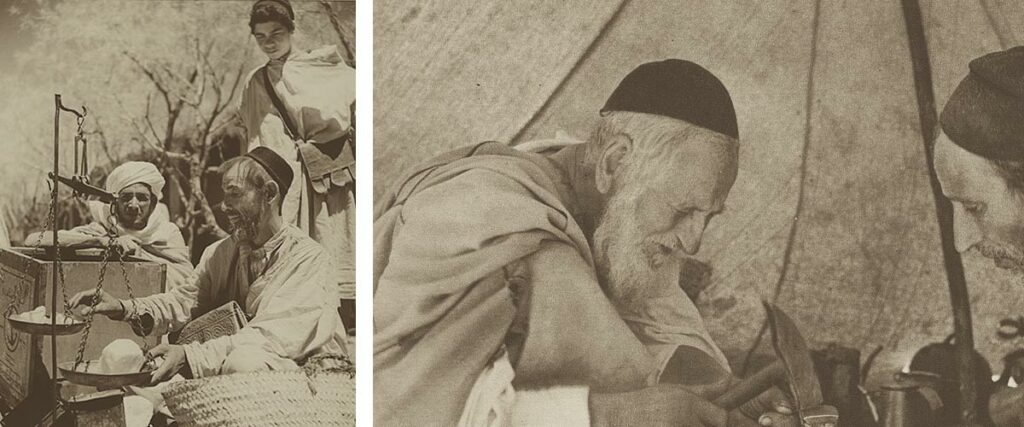

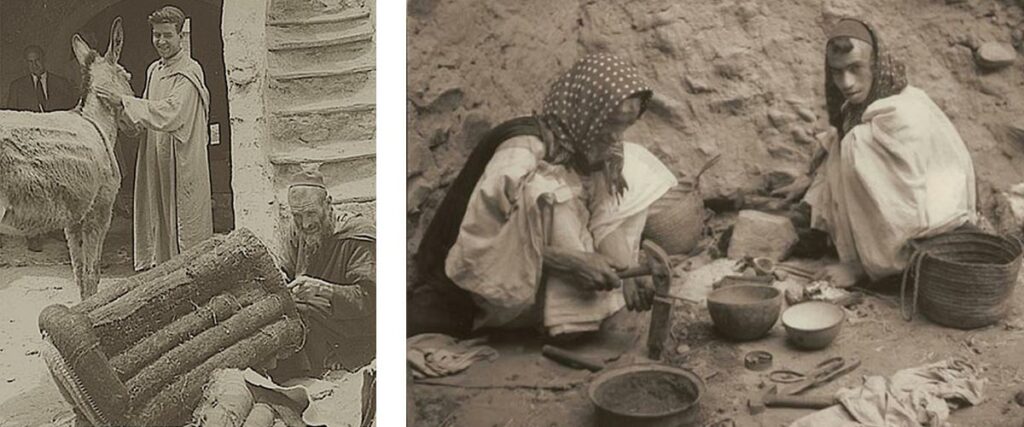

Jewish expertise and know-how serve collective interests

While the Jews of the large imperial cities often played important political and economic roles with successive sultans, as influential advisers, financial managers or diplomatic agents, their role in the South Eastern territories was highly significant in the development of localities and the organization of their economy.

The prosperity of the Trans-Saharan trade was largely based on the involvement of the Jews thanks to their ancestral knowledge of the desert and nomadic life. This know-how, enhanced by their perfect command of local languages, enabled them to open up many trails between remote regions, thus encouraging their craftsmen, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, gunsmiths, locksmiths, seamstresses, shoemakers, saddlemakers, slipper-makkers, rug and blanket manufacters to participate in weekly souks.

A perfect example is given by Rabbi Mordecai Aby Serour of Akka, who accompanied French explorer Charles de Foucauld on his reconnaissance trip to Morocco in 1883.

Around the year 1070, the Andalusian geographer Al Bakr describes the Jews living in Sijilmassa as specialists in masonry and architecture. Throughout the South East of Morocco they were seen as the builders of many kasbahs and ksour, and as the engineers of many agricultural equipments, especially for irrigation.

However it was in trade that the Jews gained a lasting reputation for their ingenuity and efficiency. A popular saying nicely illustrates this fact :

The Jew in the souk is like leaven in bread.

Popular saying

Uprooting as a symbol of heartbreak

The 20th century was going to cause profound upheavals within the Jewish and Muslim communities of Morocco that had been established over precious centuries.

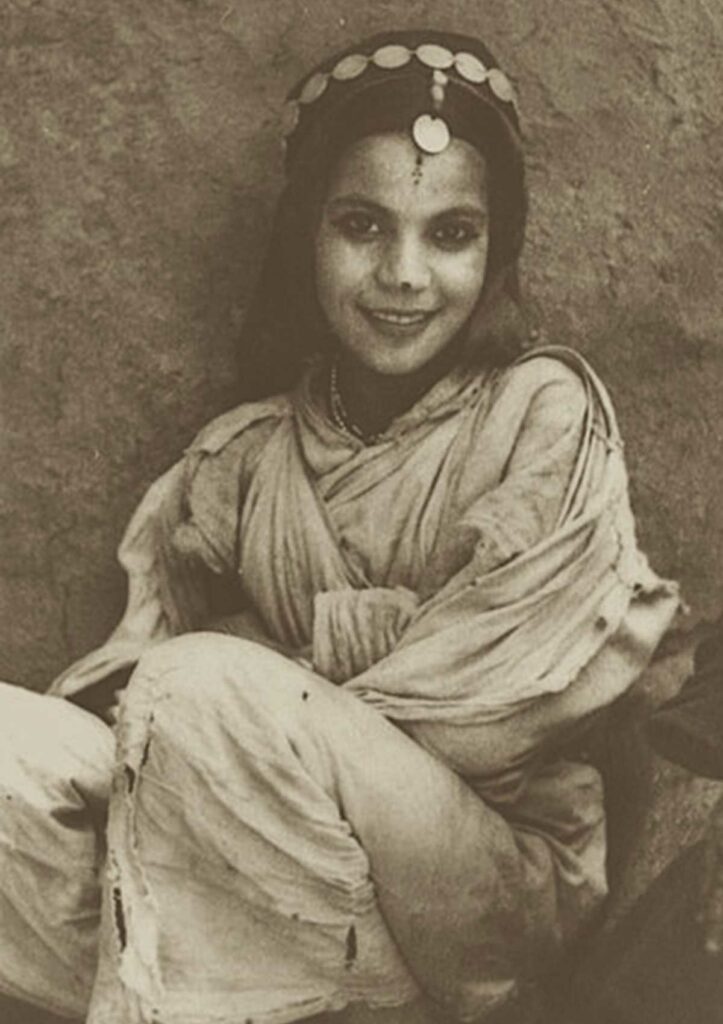

The French Protectorate established in Morocco since 1912 led to the exodus of Jewish families from rural areas towards the largest cities, motivated by the desire to access Western modernity, and with the secret hope of emancipation. While France provided support for the development of modernized education on the French secular model, the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU), a French organization, offered massive schooling for young Jewish girls and boys, especially among the poorest families, and therefore mostly in rural areas of Morocco.

The second half of the 20th century, from the independence of Morocco and the various conflicts between Israel and Arab nations, will lead to the departure of the vast majority of Jews from Morocco, although they had become Moroccan citizens.

Mrs. Fadma from Ouarzazate, who died of Covid 19, then aged about 120, remembers these moments of separation with regret:

« The Jews mostly lived in the village of Telmasla. They were never our enemies. We lived together. I still remember that day when buses arrived in our villages to take them. We all gathered to say goodbye to them. It was a sad day. »

Mrs. Fadma

The eclipse of Jewish communities in the national narrative of Morocco

More than two thousand years after their arrival, the signs of the presence of Jewish communities in the south-east of Morocco have been gradually disappearing. Some traces can still be found in the name of villages or families, in popular legends or local customs. While oral traditions still preserve some memories of all these living communities among Berbers, Arabs and Jews, it is feared that time may erase all of them forever if nothing occurs to enhance and preserve them. This would eclipse the share of the Jewish community in the national narrative of Morocco even more.

The story of Jewish contribution in building Morocco remains unknown, especially among younger Moroccans. Although a few initiatives have been launched in Morocco’s larger cities to counteract this historical amnesia, thus giving the collective story a tapestry of color, nothing has yet been done here in South East Morocco, just as with other facets of the rich memorial mosaic of this region.

A testimony from a Moroccan Jewish woman who moved to Israel expresses a clear wish:

« I want young people to know the history of Moroccan Jews. In the villages, Jews and Muslims were full brothers. The Jewish mother breastfed the baby of the Muslim mother and vice versa. We never abandoned our country. Three generations of Jews linked to Moroccan origins born in Israel. Grandparents travel every year with their grandchildren to Tinghir, Skoura, Errich and elsewhere in Morocco to pay homage at the tombs of their ancestors and their saints (Tsadkim). »

Fanny Mergui, born in 1944 in the medina of Casablanca

The mystery of this Jew, Moroccan forever, remains intact

Finally, once pilgrimages have ceased and all memories have vanished, there will only remain the unalterable scars of heartbreak caused by this mass exodus of Jewish communities from Morocco. The tearing apart of entire families torn from their native land, and land of their ancestors. The tearing away from a country that had become theirs. And many Muslim Moroccans felt a similar heartbreak when they helplessly watched the departure of all those with whom they had, over the centuries, the experience of having become Moroccans, despite everything, despite periods of persecution, constraints or bullying.

The history of the Jews in Morocco unfolded over a very long period, where light and shadow intermingled, as a faithful reflection of the progress of humanity. However, a remarkable fact can be observed and all testimonies confirm it: this Moroccan Jew, whether from the south-east of the country, from other rural areas or large cities, has left the country. But wherever he is in the world, in Israel, in Europe, in Canada, and everywhere else, he carries with him, alive and present, his Moroccan component.

Between the sufferings and the beauties of his life in Morocco, the mystery of this Jew, forever Moroccan, remains intact.

This mystery undoubtedly sheds light on the past of all Moroccans and all Morocco’s territories. This may also illuminate their future if an awakening of memories were to be permitted to rekindle this light, in all its hues, of the great and beautiful story of Morocco, as a kingdom fully proud of its plural identity.