The Ksar of Ait Ben Haddou held a familiar embrace for Loubna. She holds memories of those rare childhood moments spent here during vacations, reuniting with grandparents native to the place. She recalls her childhood games amidst the labyrinth of dusty streets, the communal basin swims, the horseback rides. However, the essence of her life unfolded in Agadir, and in Casablanca for her higher education. Today, she holds the profession of an airline pilot at Royal Air Maroc.

Her patronym, Mouna, immediately signifies her belonging to these lands as it bears the name of one of the five prominent family lineages that have formed a community here since ancient times. Her father, Ahmed Mouna, born here but raised and lived elsewhere, remains a renowned figure, having passionately advocated for the UNESCO classification of the ksar as a World Heritage Site in 1987. While based in Agadir and a successful entrepreneur, he committed himself to supporting the territory’s development during a time when the southeastern region was entrenched in poverty, far from the dynamic pulse of Morocco, distant from everything. He did so out of gratitude to the land of his own parents, yet he never built a family home here, and these native lands became but a fleeting memory for all.

Aït Ben Haddou (in Tifinagh: ⴰⵢⵜ ⵃⴰⴷⴷⵓ, in Arabic: آيت بن حدّو) is a ksar (Ighrem, in Berber) in Morocco. “Aït” means “family.”

Years later, when Loubna returns to the Ksar of Aït Ben Haddou, she knows no one, and no one recognizes her. The site has become an unavoidable stop for all tourists passing through Morocco, eager to cast a fleeting glance upon the Amazigh world. The alleys teem with vibrant bazaars. Guides, whether official or impromptu, pounce on every newcomer. The bottleneck of visitors is perpetual, their flow swift. Her plan to settle here fails for mundane reasons, and as she goes in search of another promising place elsewhere, she falls seriously ill to the point of being unable to walk. Confined to her bed and subjected to numerous medical procedures, Loubna begins to search for the meaning of this sudden and radical trial. In this intimate confrontation, she realizes that the name Aït Ben Haddou still resonates within her, and she understands that she must uncover the significance of this connection to the land, and above all, its purpose — that is, to understand what to make of this bond in her life.

The tale of the ksar mirrors the story of Morocco

Emerging from her convalescence, it becomes evident that she will meet her parents to ask them to recount the history of this land that resonates within her so deeply. Their response acts as a catalyst: they know nothing of this history, as it has never truly interested them. Their parents are deceased, taking with them all their memories. Loubna thus has no choice but to return to the site to attempt to uncover the answers to her questions. She decides on an initial journey accompanied by her mother, and a second one with her father afterward. During the first journey, and thanks to her mother’s presence, she is no longer a stranger. She is Haj Mouna’s granddaughter.

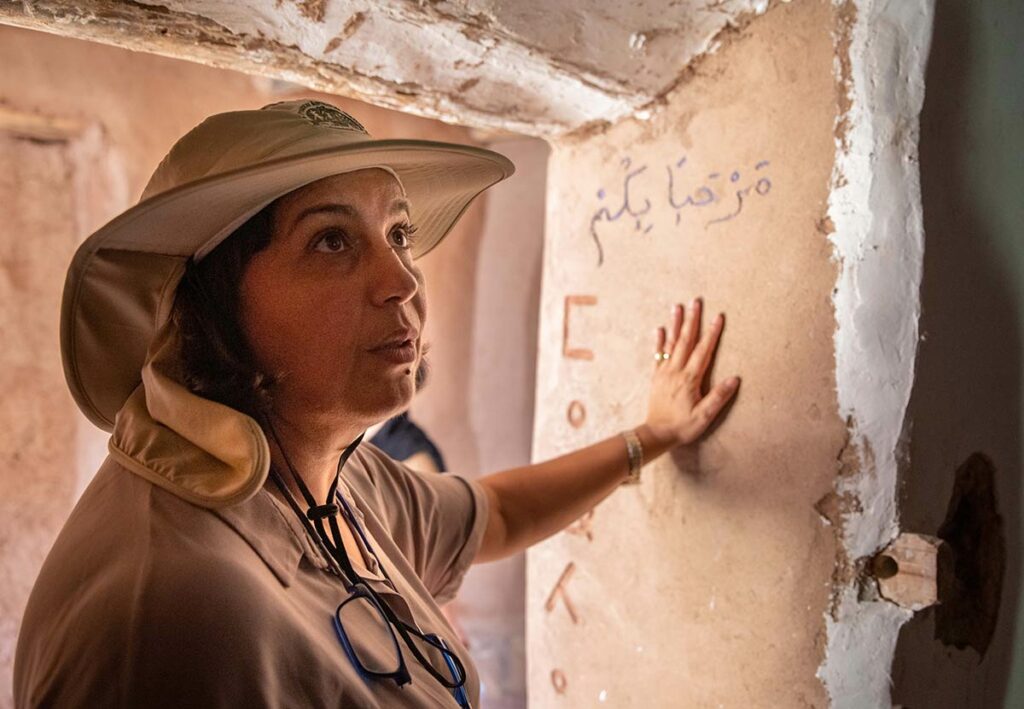

A distant cousin leads her to meet the elders of the ksar, starting with an old woman who welcomes her with open arms and recites an ancient Amazigh poem with a strong voice, traditionally spoken to greet a visitor not seen for a long time, signifying a warm welcome. At that moment, Loubna understands little of the Amazigh language, but her tears flow endlessly, like water from a long-lost spring. She visits another old man, and then another.

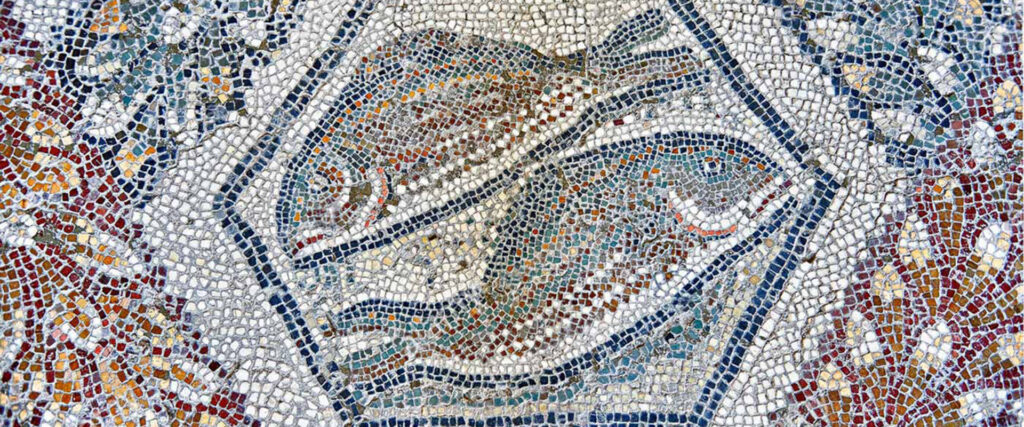

For the first time in her life, she listens to the history of her original community and the place of her ancestors, the Ksar Aït Aissa, renamed Ksar Aït Ben Haddou in the early 20th century. There, she understands that the history of this small patch of land, where her roots lie, mirrors the history of her country, Morocco: a mosaic tale formed from the meeting of multiple cultures, a crucible where humanity blends from one to another.

A first glimmer of an answer takes shape: she will do everything necessary to ensure that this radiant memory is preserved, before the passing of its living witnesses, and can thus be shared both in Morocco and throughout the world.

The walls of a territory cradle the memories of its communities

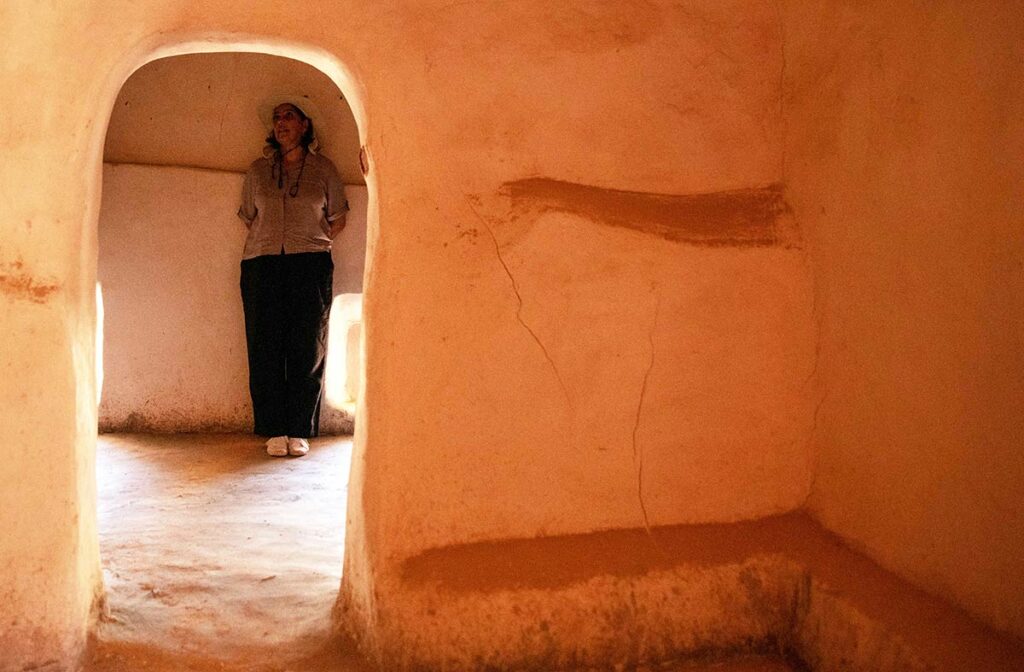

During a second visit with her father, as she wanders through the alleys of the ksar, she discovers the damage caused by the torrential rains that had fallen on the South of Morocco in the preceding months. All the rehabilitation work carried out a few years earlier under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture was almost completely undone. Despite being classified as a World Heritage Site, the site seemed destined to disappear with the whims of time, and no one in the douar felt capable of fighting against this fate. As the roofs and walls crumbled into dust, joining the wadi that flowed at the foot of the ksar, the history of the place faded away, memory after memory, until it merged into the unfathomable sea of oblivion.

A second response is imperative: to breathe life back into the walls of the ksar so that they become the cradle of the memories of its human communities offered to passing visitors. The roadmap is now clear. Loubna and her partner have found the project that will occupy their future. They decide to revitalize the local association Aït Aissa, founded by Loubna’s father, and launch as a first step a lengthy phase of participatory dialogue within the local population, so that everyone can collectively express who they are, where they come from, and together envision where they want to go in the future, for their children, for their territory.

A first observation arises: the human community of the ksar needs to revive the collective spirit. The Amazigh New Year celebration, the festival of seeds and earth, will be an opportunity to gather the population in a joyful atmosphere. On January 13, 2016, under Loubna’s impetus, this first collective celebration is organized under the title “we are all one.” It is a success. Doors open, neighbors take the time to talk to each other, the elders gather again, and children play together. Then, in April 2017, the Aït Aissa association organizes the first “Heritage Day” under the theme of “community life” to welcome tourists for free and allow them to experience the charms of daily life in this emblematic place of southeastern Morocco.

Loubna and Hicham mobilize their friendly and professional contacts in Casablanca, Rabat, and Marrakech to gather the expertise necessary for the implementation of the future project, which takes shape through collective discussions among the inhabitants of the ksar. Establishing a place to generate income for the members of the women’s association of Aït Ben Haddou; this is the Tawasna tearoom in a garden of the ksar, a place that is now fully active and profitable. Reviving agricultural projects to diversify the territory’s economy and no longer depend solely on tourist activities. Organizing the sale of regional products through a Cooperative House. Showcasing the traditions, rituals, and rites of the ksar in an Oral Traditions House. A Cinema House to promote the cinematic history of the ksar. Thematic tours of the ksar to provide local guides with an organized and diverse offering (tours focusing on rites, cinema, ksar history, and three family homes ready to welcome visitors to present beauty rituals, daily life, and weaving). All of these activities, with an initial launch planned for November 2019, will generate funds, part of which will be pooled under the supervision of a council of elders to finance preservation and promotion work on the ksar.

A new association is created to bring together all these human expertise from the major cities of Morocco, mobilized by Loubna and Hicham, the “We Speak Citizen” collective, which aims to support the development of rural areas in Morocco, with the project carried out on the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou serving as a laboratory for the emergence of a new way of fostering rural growth in Morocco.

The lasting gold of a community is its intangible heritage

The development approach implemented in the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou set forth a crucial initial step: a dual awakening within the population. The first must lead the people to understand that the fate of their territory, however renowned it may be, cannot rely solely on the immediate exploitation of its assets—here, old dwellings and rows of traditional objects—but must be grounded in the recognition that true value, the enduring gold that withstands the test of time, is intangible. It is essential to preserve ways of life, communal rites, daily rituals, oral histories—all that once nourished the community’s identity and sustained its collective spirit.

The second awakening must lead this same population to realize that they themselves are the sustainable solution to their territory’s problems. It is the pooling of collective talents and their cooperation in service of the common good that will render any development action effective and robust, whether undertaken by the state, institutions, or private organizations.

Loubna’s gamble, her intuition, lies in recognizing that it is precisely the embellishment of this intangible heritage, its showcasing and promotion in broad daylight, before the eyes of the world, that will once again nurture the identity of the human community of Aït Ben Haddou and revive its collective spirit. It is this enhancement of the collective being that will nurture the pride of its members and enable them to transcend personal interests—not to negate them, but to harmonize them in a synergy that brings good to all.

The re-enchantment as a driver of development

The equation posed by Loubna, Hicham, and their colleagues is clear: for a collective facing the necessity of growth and development, the recognition of beauty within it, the embellishment of its identity and nature, is the most effective lever for mobilizing its vital forces and taking control of the mechanisms of this development.

The greatest challenge Loubna must confront, and she is aware of it, is the widespread defeatism that too often leads to the belief that nothing new is achievable in Morocco. It is also, and above all, the equally widespread propensity for indifference that allows for the disappearance of memories, the forgetting of history, the loss of roots, and the denial of the pluralities that have constituted the ksar here and everywhere else in Morocco. Fortunately, Aït Ben Haddou had the chance to encounter one of its own who was there at the right moment to give it the impetus it needed to awaken. It is done. Projects are underway, and others will follow.

Emerging from illness, Loubna Mouna Guenoun reached a tipping point in her consciousness that led her to serve the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou. Through the words of the elders who welcomed her back among them, Loubna discovered an ineffable strength that suddenly re-enchanted her being and, consequently, her life. For it is in this reconciled, peaceful time—where harmony reigns between the past, the present, and the future—that the individual and collective being finds the true space for its growth and the matrix of its joy. And that is what was missing for Loubna. It is from this same re-enchantment that the success of the project undertaken with the population of Aït Ben Haddou, or the mobilization of third-party expertise and necessary financial resources, arises.

Undoubtedly, the ongoing laboratory in the ksar of Aït Ben Haddou will serve the rest of Morocco and all its rural areas: the re-enchantment of the origins of a collective and its journey traveled is the guarantee of the success of its destiny.

Photo credits : Abdellah Azizi / azifoto.com

2 responses

What a delightful discovery this project and story of a life journey have been… it reignites my desire to rediscover the ksar in a different light. My best wishes for the success of this collective project. Thank you for sharing; it’s a pleasure to find Eric Anglade’s pen and Abdellah Azizi’s always inspiring photos once again.

Good evening,

I discovered this ksar. One is captivated by these dwellings. There is a soul. There is an inn managed by Moroccans that surprises you with its uniqueness and decoration. Worth discovering: it’s featured in the backpacker’s guide.

I discovered the land of my ancestors, Oulad Haddou.

Azeddine Daoumer