T he Berber world is like a world in itself, full and vast of a history that plunges into the distant past of our humanity, rich and colorful with a morning identity from its roots to the three horizons, solid, almost mineral, and yet vibrant multiple resonances of its culture. It is now recognized that Amazighity is an integral part of Morocco’s identity, at the very least of its unity, as clearly stipulated in the new Constitution of 2011.

Sudestmaroc.com takes you to discover this Amazigh world by starting a first journey with the observation of its culture under the gaze of a personality who is both expert and passionate about his subject. Dr. Mohamed Chtatou thus answers our questions.

Mohamed Chtatou – The Berber, self-named Amazigh – in the plural Imazighens – is one of the descendants of the pre-Arab inhabitants of North Africa. Today, Berbers live in communities scattered across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Mali, Niger, Mauritania and Canary Islands. They speak several Amazigh languages all belonging to the Afro-Asiatic family related to ancient Egyptian. These Berber populations have been present in this continental region since the Upper Paleolithic.

The Upper Palaeolithic is the period of prehistory characterised by the development of certain techniques (flakes, tools and weapons made of hard animal materials, propeller, etc.), while at the same time there was an explosion of art. The Upper Palaeolithic extends from about 45,000 to 12,000 years before the present. (Source : Wikipedia)

The indigenous population of North Africa was formed by the arrival of several waves of people, some from Western Europe, others from sub-Saharan Africa and still others from Northeast Africa.

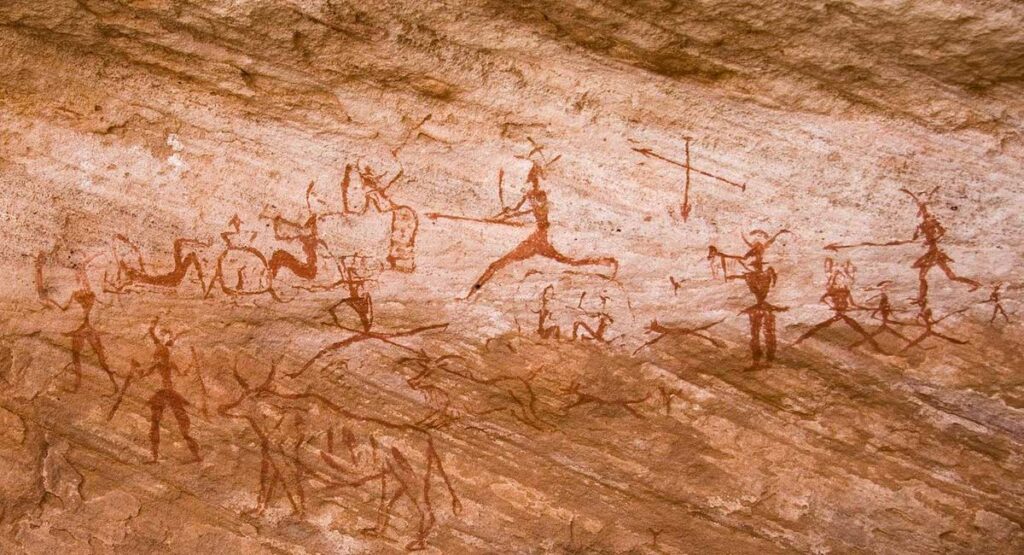

The origins of the Berber peoples are not clearly known but their history is long and ancient, much of which is unknown to us because these peoples did not have a written language at the time. The first clue to their history was the discovery of cave paintings. Indeed, 12,000-year-old North African cave paintings have been spotted in Tadrart Acacus, Libya. Many of these paintings depict agricultural activities and domestic animals. Paintings have also been found in Tassili n’Ajjer, in southeastern Algeria.

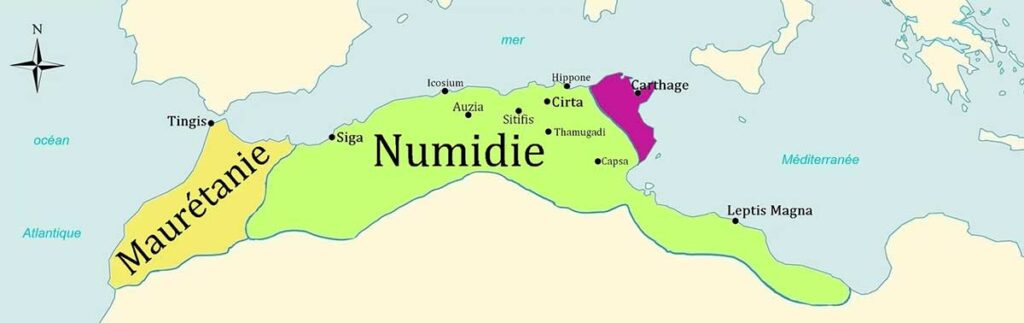

From around 2000 BC, the Berber languages spread westward from the Nile Valley to the Maghreb, passing through the northern Sahara. In the first millennium BC, their speakers were the native inhabitants of the vast region visited by the Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans. A series of Berber peoples – Mauri, Masaesyli, Massyli, Musulami, Gaetuli, Garamantes – then gave rise to Berber kingdoms under Carthaginian and Roman influence.

Among these kingdoms, Numidia and Mauritania were officially incorporated into the Roman Empire at the end of the 2nd century BC, but others appeared in late antiquity following the Vandal invasion of 429 AD and Byzantine reconquest of 533 AD, only to be suppressed by Arab conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries AD.

MC – We can distinguish two main Berber cultures: that of the north, in the countries bordering the Mediterranean, and that of the south in the Sahara and the Sahel.

The Berbers of the North received the denomination of Imazighens and those of the South of Tuaregs. The Imazighen are mostly sedentary with a nomadic minority and the Tuareg are mostly nomadic. The Imazighen are found from the Siwa Valley in Egypt to the Canary Islands via Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. The Tuaregs in Mali, Niger and a tiny part in Burkina Faso.

MC – First of all, the traditional Berber community has as its basic unit the nuclear family, generally patrilineal. Starting from this unity, the tribal group is composed by the reunion of several families gathered around the name of a common ancestor. It is also from this founding name that the tribes acquire a public identity. They use the name Aït, which means people or family, followed by the name of the common ancestor.

In principle, all families within a tribe are equal, governed by a code of honor under the authority of a council of elders, the jmācath (democratically elected political entity) which maintains harmony within the community and act of judgments in the event of conflicts, in particular to fix compensations and determine punishments.

In fact, the different Berber societies were not so egalitarian. The tribe regularly admitted new people to their village, but they were then considered inferior. More generally, the elders who held power often came from the same ruling families.

The Tuaregs, a people of aristocratic nomads

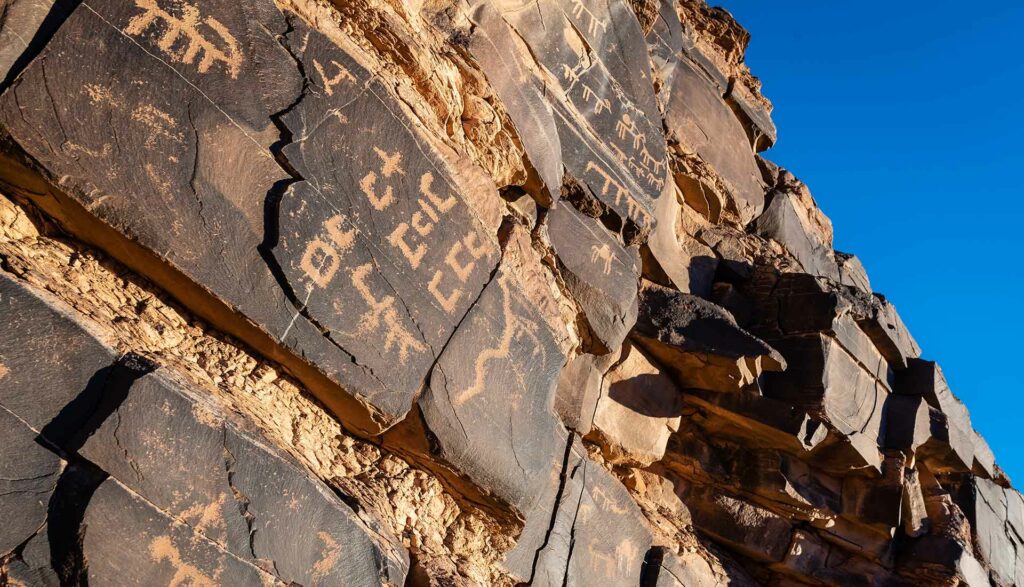

The Tuaregs of Ahaggar and southern Sahara, also known as “blue men” because of their indigo-dyed robes and face veils, were aristocratic nomads who ruled over vassals, serfs and slaves who cultivated the oases in their name; they in turn recognized supreme chiefs or kings, who were called amenukals. The Tuaregs have retained a form of the ancient Libyan consonant script under the name Tifinagh, although most of the script is done in Arabic by a class of Muslim scholars.

MC -One can distinguish three main themes in the Amazigh culture which constitute an important and primordial trinity in its system of values. These themes have transcended Berber culture and have been widely accepted as core concepts of Moroccan identity.

The trinity in question revolves around the following notions: first, we distinguish the importance of language as a vehicle of culture and the main marker of identity (Tamazight/awal) both in terms of communication and the perpetuation of history. Then there is the omnipresence of the strong and indivisible system of kinship and belonging to the extended family (ddam/tamount) which is expressed by solidarity and coexistence. Finally, there is the strong connection to the earth and the identification with its benefits and the belief in its sacredness (akkal/tammourt/tamazirt); this last identity marker is very strong among other peoples around the Mediterranean.

The most obvious theme, which is present in the Amazigh community in Morocco, is the importance of language in society, civilization and life. When one contemplates the culture of the Amazigh people, there is a clear correlation between the relevance of the language and the preservation of civilization and millennial traditions. This is the case, for example, of the Master Musicians Jahjouka in the northeast of Morocco. Their trance music and anthropological theater has gone through four thousand years of history without a scratch.

The history and belief system of the Amazigh people have been preserved orally from father to son; where one generation transmitted history, wisdom and laws to another, automatically through the mother tongue, a powerful linguistic vehicle. In reality, despite the existence of three distinct Amazigh dialects in Morocco, the history and laws of the Amazigh people have synchronized and survived countless invasions through a long history of eight millennia.

The matriarch as the pivotal person of the Amazigh family

However, the idea of kinship that manifests itself through people related by blood, experience and history shows a relevant distinction between Amazigh and Moroccan culture in the sense that the Amazigh community system emphasizes the notion of the matriarch as the pivotal person of the family imbued with democratic values, while Moroccan culture, of Arab substrate, prefers a patriarchy, very strong and undivided.

Among the Amazighs, blood ties are sacred in marriage, paternity and family affiliations. Indeed, two tribes sign their alliance by a marriage. Blood, in the context of sacrifice, is also a sign of reconciliation, of asking for forgiveness and of respect (tagharst). It is also the symbol of hospitality, a sheep is slaughtered to welcome a guest or any stranger because to shed blood is to establish a bond of respect with the newcomer and include him in society and in the community, the jmacath.

The earth, a sacred good

The Amazighs regard the land as a sacred good which not only supported life, but provided protection against Western and Arab imperialist campaigns and which also helped to preserve the language and the community system. Moreover, the sale of any inherited piece of land has been a strongly stigmatized notion (Hshuma) in the Amazigh culture of always.

The Amazigh civilization has survived the wear and tear of time and invading cultures thanks to the infinite love that the natives of North Africa have for the land that nourishes, protects and strengthens them. We can also see that Amazigh has managed to defy time because the mountains (akkal) have protected it against acculturation and invasion.

The love of the Amazigh for the land is manifested in agriculture and during festivals celebrating its benefits for the community. We find such celebrations among the ancient Amazighs of the Jbalas, in particular the Aït Serif clan with their oldest musicians in the Mediterranean, the Jahjouka, who celebrate the fertility of the land in music and dance during their annual festival known by the name of Boujloud in Arabic and Bou-Irmawen/Ilmawen in Tamazight.

MC – The history of the Berbers living today in Morocco, Tunisia, Algeria, Libya and Egypt, is deeply marked by the domination of groups of populations from elsewhere – first by the Romans, then by the Arabs, and later by the French, Spaniards and Italians.

“Adaptation and rebellion” – these were the only options open to the Berbers under foreign rule. As free men, that is how the term Imazighen can be translated into English, they mostly opted for non-adaptation and retreated to mountainous areas to practice their culture in their families and escape prosecution from foreign rulers.

Tattoos were one of the means of rebellion. The signs and ornaments that decorate the backs of men’s hands speak of tribal affiliation and religion – and they were banned under Muslim rule.

To counter its assimilation in the face of the cultures of the conquering peoples, the Berbers were able to ensure their own cultural continuity throughout history thanks to their arts and the identity symbols that were thus conveyed. Music obviously played an important role. The ancient Berber culture is extraordinarily rich and diverse, with a variety of musical styles. These range from bagpipes and oboe (Celtic style) to pentatonic music (reminiscent of Chinese music), all combined with African rhythms and a very large stock of authentic oral literature. These traditions have been kept alive by small bands of musicians who travel from village to village, as they have done for centuries, to enliven weddings and other social occasions with their songs, stories and poems.

The mother, vector of Berber cultural continuity

Berber mothers have been largely responsible for the survival of the Berber language and cultural identity. Mothers share traditional stories and beliefs with their children. Women also preserve cultural traditions through handicrafts, such as tapestry, jewelry, tattoos, and pottery.

Rural women, especially those who are illiterate, preserve Tamazight as a living language, infusing traditional art forms with a certain orality to transmit linguistic traditions from generation to generation. In the realm of music and poetry, Amazigh women use their verses to keep the community informed of the movements of different members, to recount important events, to uphold moral and social codes, and to remind the wider community the ties that unite them and their common memory.

MC – Although anthropologists say that it is difficult to establish with precision the possible historical roots of the Berber New Year, known as Yennayer. Some historians link it to the enthronement as pharaoh of the Amazigh king Shashnak after defeating Ramses III, in 950 BC. The Amazighs thus succeeded in establishing a kingdom that stretched from Libya to Egypt. This glorious victory would have marked the beginning of the Amazigh calendar.

The Amazigh New Year marks the first day of the agricultural year for Berber communities. It corresponds to the first day of January in the Julian calendar. The year 2020 thus corresponds to the year 2970, and the day of the new year is around January 12 in our usual calendar. The Berbers sometimes call this festival “Id u-Suggas“, which means “night of the year”. And Arab communities call it “Hagouza“, which means “Agrarian Year”.

The Julian calendar: is a solar calendar used in ancient Rome, introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BC to replace the Roman Republican calendar. It was used in Europe until it was replaced by the Gregorian calendar in the late 16th century. There is a 14-day difference between the Gregorian calendar and the Berber calendar.

The Berber people celebrate Yennayer in Morocco, Libya, Tunisia and parts of Egypt. The Algerian government recognizes it as a national holiday. In Morocco, many people are working to have Yennayer recognized as a national holiday as well.

As an agricultural holiday, Yennayer is a celebration of life. Like the January 1 holiday, it is a time for people to wish for longevity, prosperity and the future. It is a day for weddings and other important life events. Children go through important rites of passage during this Yennayer holiday. Boys may receive their first haircuts. And parents send their children to get fruits and vegetables.

Food is an important part of the celebration and several dishes are traditionally served on this special day. Orkimen is a thick soup made of dried beans and wheat. Couscous is another traditional dish, and on Yennayer it is specially prepared with seven vegetables. Tagoula is a meal of corn grains prepared with butter, ghee, argan oil and honey.

A date seed or a piece of almond can be hidden in the Tagoula or couscous. Whoever finds the seed or nut is supposed to be blessed throughout the year. In the past, this person was entrusted with the keys to the storage room for the rest of the year.

There are also many amazing traditions and practices that accompany the food that the Amazigh prepare for this festive night. In addition to the special dances and songs of love, fertility, and prosperity that welcome a new agrarian year, the Amazighs, especially those living in the countryside, find this occasion a better chance to socialize, exchange food, and reconcile with those with whom they have had some misunderstanding.

MC – The orality of women, most of whom are illiterate, is a major factor in the survival of Tamazight, as they use this language in domestic communication, raising children, and repeating folk stories, poems, proverbs, songs, and family and cultural stories. Because Tamazight and related Amazigh languages are not taught in public schools, it is incumbent upon Amazigh women to pass on knowledge of the language to subsequent generations. And as primary caregivers, women are the children’s first link to Tamazight, giving the language its mother tongue status and consolidating its longevity despite its lack of representation in the public sphere.

Another reason why women can be considered the primary actors in the preservation of Tamazight lies in their related role as custodians of culture. In addition to managing their homes and raising their children, women play a vital role in preserving Amazigh artistic and cultural heritage through their work in areas such as textiles, music, poetry, and dance.

Again, women are particularly important because they infuse these arts with traditions passed down orally from generation to generation. For example, women give Tamazight names to their textile designs and pass them on to their daughters. The names vary depending on the similarity the weaver imagines between the pattern and surrounding objects or the natural world, so that a single pattern may have a multitude of descriptive Tamazight names for different artists and families.

Moroccan Amazigh rugs are unique and have a fascinating history. They are one of the most famous folk art carpet styles. These carpets have been made continuously for over two millennia. The weaving of Moroccan carpets has always been the responsibility of Amazigh women both in terms of creation, weaving and artistic representation.

Women were responsible for preserving and transmitting the knowledge necessary for the manufacture of these carpets, including the secrets of family patterns, looping techniques and the colors to be used. All of this knowledge about the history of Amazigh carpet weaving was passed down matrilineally, with each generation of women responsible for passing it on to the next. Carpets were used within tribal groups as house covers, horse blankets, standards, flags and other utilitarian objects.

MC – Although they have retained the language and many of the customs of their Berber ancestors, the Tuareg have developed a unique culture of their own, a true synthesis of many traditions, including not only Berber and Arab, but also elements of indigenous peoples who reside in the Sahel.

An aura of mystery and romance surrounds the desert nomads known as Tuaregs. Long known as warriors, traders, and skilled guides in the arid, harsh Sahara Desert, the Tuareg have seen their independence severely threatened by recurring droughts that kill their herds and by international borders that severely restrict their travel. Many have been forced to abandon their nomadic lifestyle and settle down, forming small villages or moving to cities to find work.

Berbers once sought refuge in the oases of the Sahara

The Tuareg people represent a Saharan offshoot of the Berbers, who have resided in North Africa for several millennia. While today’s Tuareg are nominally Muslim, their ancestors fled to the Sahara Desert to avoid submission to Arab conquerors and conversion to Islam. Following the Arab conquests in the seventh century A.D., and then the Bedouin immigrations to North Africa in the eleventh century A.D., many groups of Berbers sought refuge in the oases of the Sahara. There they adopted a nomadic and predatory lifestyle, modelled on that of their invaders.

These nomadic pastoralists inhabit a region of North Africa that stretches from central Algeria and Libya in the north to northern Nigeria in the south, and from western Libya in the east to Timbuktu in Mali in the west. Today there are an estimated 1.3 million Tuareg, most of whom live in Mali and Niger.

Tuareg society is traditionally feudal, with five castes: nobles, vassals, holy men, artisans and workers (former slaves). The Tuareg are traditionally monogamous and have a matrilineal inheritance system. In this, they differ markedly from their Berber relatives, the Arabs and most other sub-Saharan peoples.

MC – The cultures that make up Morocco are inextricably linked. But the Amazigh culture is nevertheless the central element of the way of life and the popular belief system dominant in Morocco. One example is the Twiza, or community support network, which is basically an Amazigh concept but has become the foundation of Morocco’s contemporary social structure.

In Morocco, Amazigh customs and belief systems are central to popular Islam, including Sufism as practiced by Sunni Maliki Muslims.

Read more : The Naciria zaouia of Tamegroute, exploration of its genesis

The relationship between Islam and the Amazigh in Morocco is mutually reinforcing. Islam is the religious tradition of the Amazigh. The Amazigh in turn color the tradition with their local languages, customs, and beliefs, some of which predate Islam. Thus the ancient Amazigh animistic belief in the religious significance of the seasons gained an additional layer of Islamic significance when Moroccan followers (sing. murid, pl. muridun) of the Amazigh Sufi Sidi Harazem associated the miracle (karâmah) of spring with this Friend of God. Popular Islamic mysticism, or Sufism, in Morocco reconstructs pre-Islamic religious phenomena through an Islamic theological medium. The Amazigh awliyâ’ Allah, or Friends of God, do the crucial work of locating the Islamic tradition in their Amazigh linguistic and religious context. Popular Sufi Islam in Morocco is thus a tradition that values both the local Amazigh cultural context and the Islamic tradition.

It should not be forgotten that the Amazigh are the original inhabitants of Morocco. They have continuously lived in this country for over five thousand years. The relationship between Amazigh culture and Moroccan society is therefore natural. The beliefs and lifestyles of the original inhabitants of Morocco are therefore central to contemporary Moroccan culture.

Mohamed Chtatou is a professor of “corporate communication” at the International University of Rabat (UIR) and of “pedagogy” at the Mohammed V University of Rabat. In addition, he is currently a political analyst for Moroccan, American, Arab, French, Italian and British media on Middle East politics and culture, Islamism and religious terrorism. He is also a specialist on Sufism and political Islam in the MENA region and is interested in the roots of terrorism and religious extremism.

One Response

Thank you for this article and insight into the Berber populations.

A captivating article for travelers discovering our Atlas regions, oases, and desert.

Also interesting for those living here and seeking a better understanding of Amazigh origins linked to history and connections with rock engravings in the Drâa and Atlas, as there are overlapping Libyco-Tifinagh Berber inscriptions that deserve further research.