Ahwach represents one of the great cultural traditions of the Amazigh communities of Morocco, an art deeply rooted in rural life, primarily found in the regions of the High Atlas and Anti Atlas. Combining song, poetic language, bodily movement, and instrumental percussion, Ahwach is a collective dance involving both women and men in synchronized choreography.

In an exclusively oral Amazigh culture, Ahwach serves as a mode of expression and transmission of individual and collective experiences within the tribe, enriched with cultural connotations that echo the ancient eras of Amazigh communities.

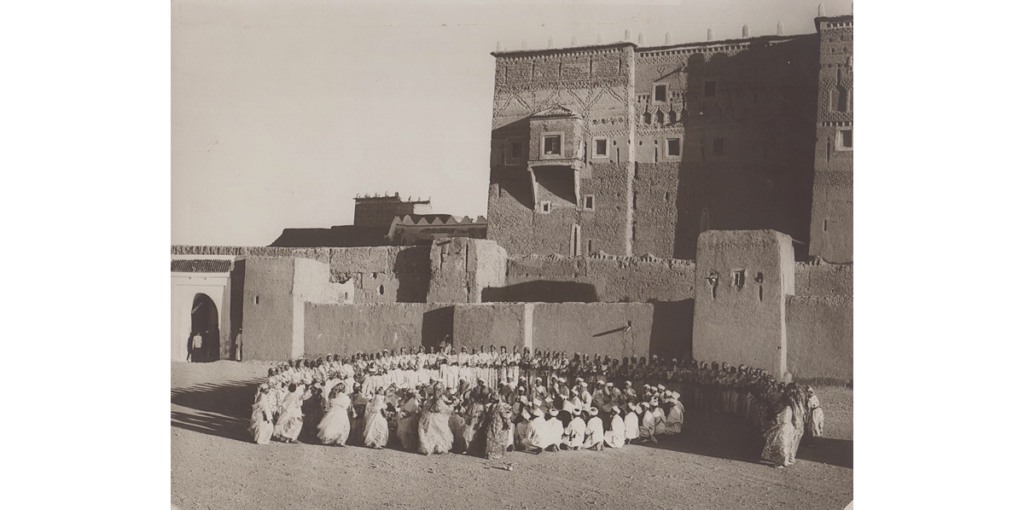

Traditionally, Ahwach took place in a central village square called “Assarag” or “Assais” in Amazigh language, serving as a communal gathering space for various ceremonies.

Clad in white djellabas and turbans, men gather at the center of the courtyard with tambourines and drums. One of them, cupping his hand to his mouth for resonance, initiates a chant with a powerful yet haunting voice, known as the Anksalim, signaling the beginning of Ahwach.

Women, adorned in white, pink, blue robes, their heads elegantly wrapped in fringed scarves and adorned with authentic Berber jewelry, form a circle around the men. The rhythmic beats of the tambourine punctuate the haunting chant, accompanied by the ululations of women. As the tempo intensifies, the women gracefully dance around the group of men, their movements undulating from low to high, while the beauty of poetry captivates the exhilarated crowd.

These women and men, united in their performance, mesmerize with their skill in verse composition, competing in the fluid expression of themes ranging from the sacred to the profane: invocation of deities, exploration of origins, heartfelt confessions, seduction, and more. This poetic discourse enriches the vibrant harmony of their synchronized movements.

The musical instruments employed during the dance primarily consist of the tara or tagenza (a type of tambourine), the tbel or dendoum (drum), and the naqus (metallic instrument struck with two iron rods).

Crédits photos : Abdellah Azizi

Ahwach remains a popular dance practiced during collective celebrations among the Amazigh tribes of southeastern Morocco. However, this nocturnal ceremony took on an official and more solemn aspect during the reign of the Glaoua caids. Enthusiastic patrons of this art, these powerful lords held sway over the entire southeast during colonial times. Attached to the splendor of their social status and institutional image, the caids ensured the enhancement of Ahwach’s aesthetics and poetry.

Thus, all the domains of the Glaoua, especially the kasbahs of Telouet, Taourirte, and Tifoultoute, were quintessential arenas for Ahwach. The Glaoua chiefs personally dictated the rules of these performances and acted as conductors. Their wives and harems would attend Ahwach shows, concealed behind the windows of their chambers overlooking the central courtyard where the festivities took place. The troupes originating from these kasbahs are nowadays the most renowned specialists in Ahwach.

For both Amazigh women and men, Ahwach serves as a space for expression and emancipation. It’s a gateway to freedom, dreams, intoxication, and fantasy… as bodies ignite in a mystical ritual where the dancer-singers create their ideal universe. Each, woman and man, is driven by the power of the desire to assert their individuality through the magic of words, born from an endless inspiration.

Ahwach is the most cherished moment for the expression of matters of the heart. Love is expressed in all its forms: betrayal, separation, budding affection, memories of love, all flow from the mouths of lovers with utmost expressiveness. However, the conservative framework of tribes and the concern for morality urge the participants to resort to a figurative style with heavy use of analogies. Only the keen and the involved, whether man or woman, can easily decipher the hidden message.

Igh ourta inni yan awal anguiss itguiwir.

Igh ourta chrriguent as mkkar tnt igna yan.

Ouada d gnnough adagh youkern ifoulan.

Wala tasmi ingha guingh laman.

Tassank as ttaggat yan trit irak.

Tasa nou assen ougguigh kiyyi anguiss oufigh.

Isso kan aggiss ttazzal oura ettenouallat.

Ddimma nnek afas nga i tassa tannalin.

A ghghad izouren s lbelght ami tousaaent.

A gghad ihwan ami douchkant f oudar nes.

Llah oualem llah ouaelm nnigh nekki.

Mra ssinhg i sra ddigrou laz i tamment.

Ikout nhsar adad i nou four tint irouh.

Attamment nou lilil dou ghroum nk a kerziz.

Adagh ifka ouhbib ifk lqoul i wyyad.

Words are controllable before being spoken.

Things are to be stitched before being torn.

It’s my sewing companion who stole my thread.

And the needle too. He betrayed me.

Look at your heart! The one you love cherishes you too.

There’s only you in my heart.

You traverse it without fatigue.

I love only you.

The first who tries on the slippers, they don’t fit him.

Those who are patient will have their rightful pair.

Maybe it’s me.

If I knew that after honey there would be hunger,

I wouldn’t put my finger in it.

It’s bitter melon honey and sour bread.

That my beloved made me taste and gave promise to another.

The singer begins by evoking his ardent passion for his beloved. He then expresses his disappointment at seeing her depart with another. Comparing love to honey and betrayal to bitter melon, he resorts to elements of nature well-known in the region. The former symbolizes happiness and contentment with its sweet and sugary taste, unlike the latter, which is a symbol of discomfort and suffering due to its sour taste.

In the past, grand Ahwach celebrations were organized with the gathering of several tribes. Each was represented by a storyteller. The honor of the community depended on the talent of its poet and their ability to “defeat” their opponents. Each storyteller-singer was thus confronted with the challenge of improvisation, and the best among them received the title of poet, known as “anddame” in the Amazigh language, in honor of the community they represented. At the beginning of an Ahwach scene, poets dare to provoke their opponents, pretending not to know them. A common stratagem to trigger the duel, as demonstrated by the following verse:

Igh Iharka yan izam iffagh tissental.

Ar ikkat s lbaroud as isslla kiwan.

A dour isker tissemzay i mattak issen.

Agh nnit a lmounad achkou niwi fllak.

Agh nnit i oujbad awrak infergh lmenchar.

Agh nnit a yazerg lhmoul rsan fllak.

Yan izdan imendi nss atmen i wyyad.

Face me! Do not hide!

Pull hard so everyone can hear you!

Beware of smallness in front of your own!

Hey amateur! You are within my reach, I’ll get you.

Pull the saw well. Beware of twisting it.

Oh Mill, you bear heavy burdens. Be careful!

The costumes and accessories worn by participants in Ahwach ensure visual communication while carrying symbolic value.

Women utilize various elements to enhance their bodies. The Tatterft, a cloth approximately six meters in length, comes in white, blue, or pink. Their hair is covered with a typical red scarf called Leqtib. The Talhzamin n’Tammassin is the traditional fabric used as a belt. They wear a piece of fabric called Tassebnit as a headband on their foreheads.

Adornments often made of silver or bronze lend rare sumptuousness to the dancers. Fibulas or Tikhllalin, plural of Takhlalt, literally meaning “thorn,” are connected by a chain from which charms dangle. This jewelry, with great decorative value, also serves to secure the Tatterft at the shoulders. The Lalwah consists of triangular silver pieces attached to braided hair. There is also the Tazra or necklace adorned with coins known as Talwizin. As a finishing touch of beauty, women apply kohl to their eyes and basil sprigs to their hair.

As for the men, they dress in white djellabas and turbans, with white or yellow slippers. Daggers and bags hang from their shoulders. While the appearance of female dancers is more elaborate, that of men remains simpler.

Various instruments are used in Ahwach, all of them percussion instruments. Some are struck with hands, others with sticks. Percussion is entirely the domain of men. The main instruments are:

– Taguenza or Tambourine: a frame drum with a single membrane equipped with a jingle, a single or multiple string that produces a buzzing sound. Etymologically, this name may refer to the buzzing sound, the “Iguenzi,” produced by this instrument. The membrane is often made of goat or sheepskin, stretched over a wooden frame and struck with hands.

– Dendoum: a cylindrical drum with two membranes, one of which is struck with a piece of pipe. Cowhides are stretched over the shell. According to some sources, the integration of the drum into Ahwach dates back to the Gnawa, as its other name suggests, Ganga. This instrument is often placed at the center of the stage and serves to set the rhythm of the music and the pace of the dance.

– Naqouss or gong: a metallic percussion sometimes made from a brake drum, lightly struck with metal sticks. It is secondary in the execution of Ahwach depending on the region.

Testimonies from travelers and expatriates residing in Morocco during the French Protectorate (1912 – 1956) provide valuable insights both on the cultural richness of the Ahwach tradition and on the significance attributed to it by the Glaoui caids.

“If Hammadi, master of Ouarzazate, has reserved us a place among the guests; tea is served by his black eunuchs in splendid crockery. Peasants constantly feed palm fires below, their reflections licking the gigantic red walls of the mansion; around the hearths, seven to eight hundred women are arranged, a fabulous vision of flashy attire in the night, purple fringed scarves, long colorful robes cinched with gold belts. They sing and dance; the dialogue of voices, sometimes shrill, sometimes hoarse like muffled cries in the dunes, follows the haunting rhythm of musicians crouched over large, deep-toned drums; and their dance is nothing but a swaying of the hips, unchanging and sensual.

Gradually, this rhythm penetrates you, disturbs you; you sway without realizing it; aided by the phantasmagorical unreality of the spectacle, your eyes close; you stagger, overcome by an inexplicable intoxication that weighs down the head, you must flee, flee quickly with fear from the mysterious temptation. Until dawn, the Ahwach of the continuous fire will continue, in a sort of frenzy, the chants intensifying, the writhing expressing with increasing violence the call to voluptuousness, while behind the bars of the only window pierced high up in the wall, the women of the harem, in clusters, will send out their ululations like cries of death.

Antinéa, Antinéa forever! A brief madness of a night for these miserable serfs of the land of famine and thirst…”

Source : Jean Ravennes.

Aux portes du Sud – le Maroc. Ed. Alexis Redier

“… She noticed, upon entering the immense kasbah of the Glaoui at night, whose huge facades and crenellated towers she barely distinguished against the night sky, the glow of a fire in the vast inner courtyard. United in a massive circle, an almost motionless dance, the women of the ksar are there, countless, adorned in their finest attire. They uniformly wear a translucent gauze tunic over the backdrop of white, cream, pink, orange, and pale blue robes, their heads wrapped in a multicolored scarf shaped like a diadem and enhanced by a golden crown or jewelry, their hair braided and wound with colored wool. This circle occupies the entire circumference of the courtyard. In the center, the palm fire, constantly replenished, casts a bright glow into the dark night…

The orchestra occupies the main position near the hearth. With their legs folded beneath them, the musicians occasionally heat their tambourines over the flame or frantically shake the copper objects they strike with abandon. The regular rhythm, in four beats, then three, eventually gets under one’s skin with its monotony. Sometimes the tambourines crack like whips or explode like gunshots…

But now, to strengthen the orchestra, the circle of women has split into two half-circles which, in turn, sing verses. The hearts alternate, respond to each other, repeat the same theme, or modify it by shifting to a lower or higher tone. Occasionally, one of the choristers, either overexcited or feeling capable of a solo, emits a series of shrill cries that break the melancholy of the refrain and can signify either weariness of life or the power of desire. However, elbow to elbow, hip to hip, without holding onto each other other than through this call of closely spaced bodies, the dancers continue to turn slowly, very slowly, swaying back and forth, in a rhythmic movement corresponding to the music, and clapping their hands in time.

Most of them are dark-skinned. Their raised hands against the backdrop of light robes create shadows. A few Berbers, tanned or even almost white, by contrast, stand out in brightness among their companions.

Then, as in a ballet, two stars break away from the troupe, whose circle immediately reforms behind them. Accentuating the movement slightly, they point their knees forward as if for a genuflection and thus advance a little faster, better illuminated by the proximity of the fire, their heads held high, almost tilted backward, their bearing proud, as if they were aware of playing a more important role, and after completing their inner circuit, return to their place to be, a little later, replaced by others…”

Source : Henry Bordeaux. La revenante. Plon 1932, roman

“… Ever since I entered, I’ve vigorously rubbed my eyes to convince myself that I’m not dreaming. I’m in the kasbah of Taourirt in Ouarzazate, one of the most beautiful in southern Morocco. It belongs to the Glaoui, whose very old brother, now eighty-five years old, has just shown us around.

It’s the Ahouach, the ancient fire dance, that we’re going to see tonight, celebrated in the deepest courtyard of the most imposing stronghold.

Outside the door, twenty torch bearers, after bowing to Colonel Chardon and myself, escorted us inside the building.

In the last courtyard, the khalifa awaited us, dignified in the folds of his spotless burnous trailing on the ground. Then followed the usual greetings: alternating in Arabic between questions and answers uttered solemnly, hand over heart, and ending, with fingers kissed, in a double murmur: Amdoullah (Praise be to God!).

Then the khalifa Si Hammadi, this old man spoken of by de Foucauld in his imperishable “Recognition in Morocco,” led us to chairs he had prepared, his remaining modestly a few meters behind.

The spectacle is captivating! In the middle of the courtyard is a blaze that a vigilant boy constantly tends to. Near him, about fifteen men, seated, have various musical instruments between their knees, which they play softly: drums, tambourines, single-string violins, while the conductor, armed with a huge mallet, sets the pace by pounding away on a barrel covered with sheepskin.

The men sing softly, slowly, a kind of chant, a lingering melody that reaches back through the ages, embodying humanity’s grateful prayer to the sacred element that allows it to live.

On the other side of the fire are fifty young unveiled women, as Berber women do not veil themselves. They are lined up in a row. All are dressed in long embroidered muslin robes, concealing, as the Koran prescribes, the charms of their bodies. Silk veils of yellow are tightly wrapped around their heads, while on their ears, on their foreheads, and along their necks hang long necklaces of coins that join the bracelets covering their arms.

With their tanned faces, tattooed in blue on their foreheads, noses, and cheeks, these women curiously stand out against the darkness of the wall before which they will dance. For the moment, they strike a hieratic pose. Motionless and upright in their immaculate veils, they remove their henna-tinted clasped hands to the height of their faces in that eternal gesture of prayer borrowed from the ancient human civilizations by all religions.

Slowly, as the music accelerates its pace, as the men’s singing rises into the calm air, they begin to animate. First their feet make a slight dancing step, then their hips sway, and finally their entire torso leans slightly forward, while their hands clap in counterpoint, following the beat of the tambourines.

Each period is emphasized with a drawn-out “La! La! La!” Until the children, inside the circle, attempt to dance. The smallest ones brought by their mothers come familiarly between our legs, and nothing is more touching than the sight of two of them, one six months old, the other six years old, the latter bringing the former near the fire.

But the music quickens its pace. One sees the white turban of the conductor plunge frenziedly into the midst of the circle of musicians. The beats are faster, more violent; the voices of the men have ceased, replaced by those of the women who stir rapidly. Then, successively, two dancers enter the circle. They are young, pretty, almost elegant despite the long robes that tightly envelop them. Nevertheless, one senses in their more supple, more agile movements that they must have a slender body, ready for the love that always precedes, even in our so-called refined civilizations, the voluptuous dance of old. With quick little steps, they come near us, swaying, they stare at us fixedly, then with a rapid movement, they flee to the other end of the courtyard. Finally, exhausted, they collapse next to the fire, which envelops them in its warm light. But their companions have not stopped; on the contrary, the dance is so lively that one can barely keep up.

Suddenly, a gong clangs. Then the women freeze, and, in a charming gesture of modesty, place their clasped hands over their faces, leaving only large black eyes rimmed with kohl visible.

After a moment, the same rhythm resumes. the fire, again tended to, throws its long red and yellow flames into the air, illuminating the watchtower built above the gate from forty meters away. Soon, fires of Bengal are lit all around. There are green, red, and yellow ones that cast a fantastic light on the narrow, high courtyard. And the Ahouach continues, tirelessly resuming the strophes of its eternal songs.

The tambourines start to moan softly again, the men to sing, while the women sway.

Always offbeat, the high-pitched chants rise. Once again, the millennia-old rite seizes its servants to the depths of their souls, carried away by their mystical faith.”

Source : Marcel Homet.

Extrait de : Méditerranée, mer impériale. Edition NRC 1937