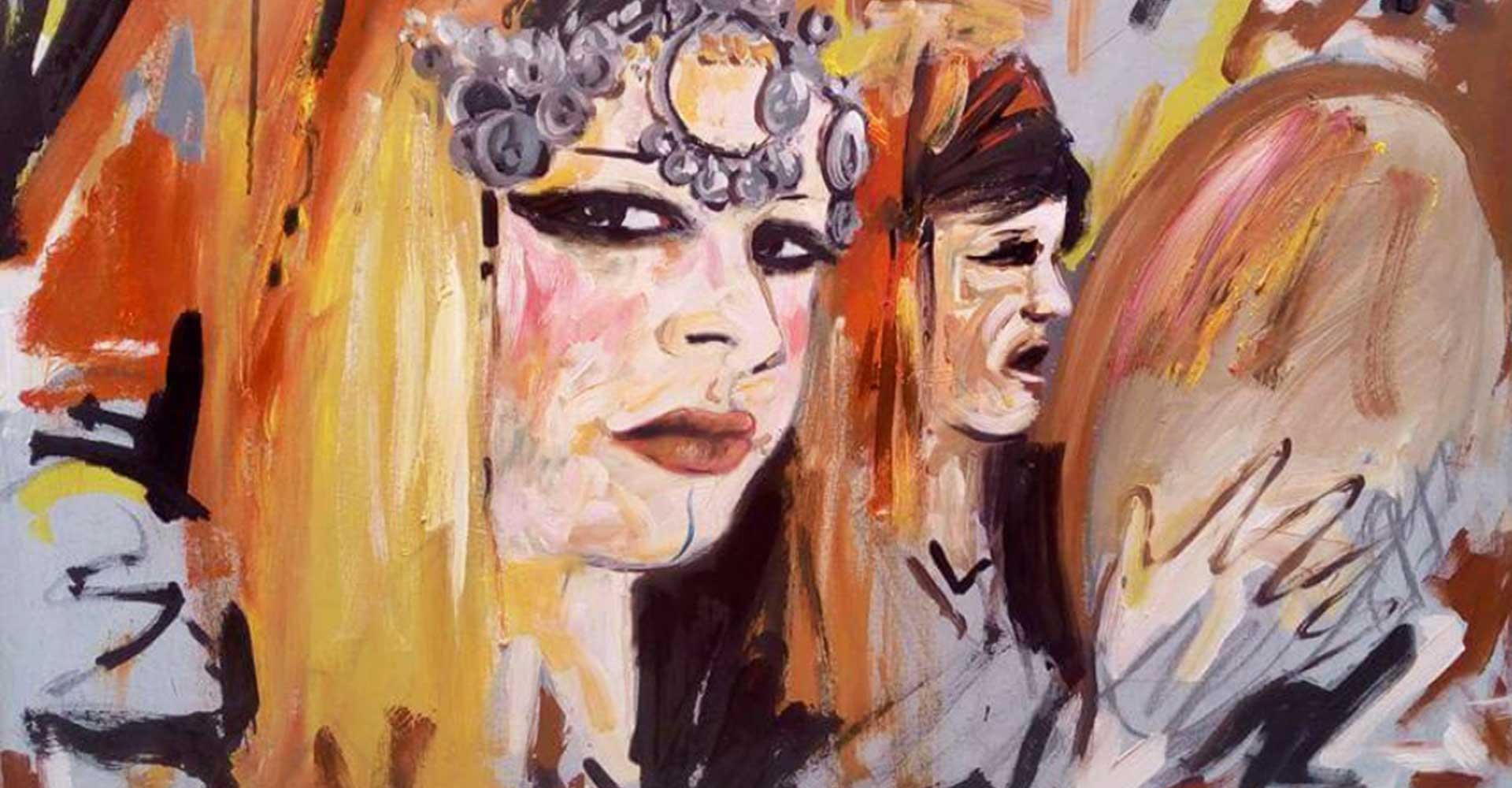

The recent passing of an iconic figure in Amazigh music, the singer and poet Idir, and the emotions it has stirred, remind us of the unique virtues of music and its ability to illuminate the most intimate colors of people’s identity, the history of the women and men who constitute them, throughout their endless and arduous paths of existence. Whether echoing myths and legends, traditions and customs, wounds and hopes, Amazigh music, both past and present, faithfully reflects Amazigh identity. In the genius of its creativity, will this music manage to carry the past into its future? Will it surpass regrets, soothe suffering, and thus foster necessary reconciliations? Southeast-morocco.com asked Moha Mallal, an artist, poet, musician, and painter deeply rooted in the mountainous heart of our region, to share his perspective on these subjects that speak to the future of Morocco.

Moha Mallal – Idir is one of the great pillars of Amazigh culture. He was born into a family environment steeped in poetry, with his grandmother and mother both being poets. His famous song “Vava Inouva” opened doors for him worldwide. Originally written and composed by Idir for the Kabyle singer Noura, the first time the song was supposed to be performed live on Algerian radio, Noura was absent, and Idir ended up singing his own song. Since that initial recording, this beautiful song has continued to be broadcasted on radios.

Subsequently, a production company based in Paris invited Idir to re-record the song. A contract was signed shortly thereafter, and the artist left his job as an engineer in the Algerian desert to embark on a very important artistic journey from Paris, which was the dream of all North African artists in the 1970s.

Idir carried the torch alongside other Algerian artists such as Maatoub Lounes and Ferhat Mhenni in defending Amazigh culture, each with their own distinct style. Known for his respect, moral integrity, skill in writing and composition, and above all, his power in choosing words, he is an irreplaceable man.

Morocco should have collectively been proud of the richness of Amazigh culture

Moha Mallal – We use our Amazigh identity, language, and traditions because we feel that our culture is not sufficiently respected in our own country. If this were not the case, if we felt genuine recognition, we would not have this reflex of defense and preservation of what constitutes the core of our identity. If there were this respect, there would be no need for this struggle or the accompanying problems that continue to negatively impact Morocco’s progress. The officials responsible for official cultural policy have committed serious mistakes toward this rich human heritage. On the contrary, we should collectively be proud of these cultural riches instead of trying to erase them, as has been the case since independence.

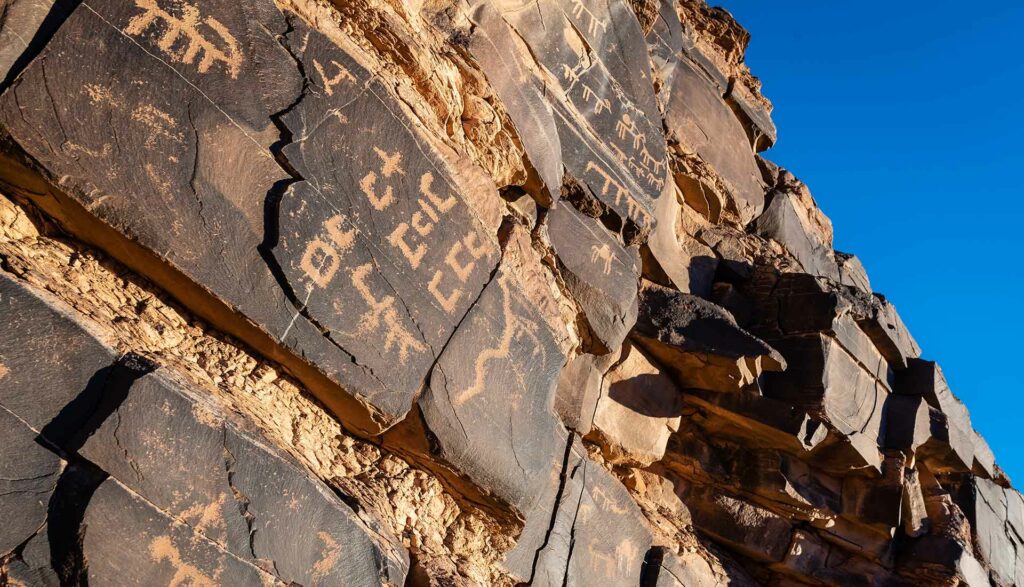

The Amazigh man is the first human of the Mediterranean and what would become Morocco. Proof of this is given by rock drawings and engravings that testify to illustrations and the Tifinagh script. It seems that Amazigh culture is among the first cultures to have appeared on Earth. Contemporary archaeologists support this theory since the revolution of genetic analyses and DNA studies.

Thus begins the defeat of all distortions of history. The question that arises is why our leaders have long denied this great Amazigh civilization and have done everything to erase it, while at the same time vigorously embracing the East, which has continuously brought us hatred and extremism. This historical reality, unfortunately so contemporary, the Amazigh people, lovers of freedom and tolerance since ancient times, cannot understand or accept it. It’s a question that will linger for a long time because it remains unanswered.

This is why Amazigh people, aware of the depth of this observation, have clearly chosen to defend their human identity through their culture, against all ideologies that have tried to silence their ideals of freedom and universality.

Amazigh culture cannot feel at ease within a single folkloric approach

Moha Mallal – The main source of inspiration for music in Morocco, as in other artistic domains, is Amazigh culture, despite the dialect in which it appears. Amazigh regions still host extraordinary rhythms such as Ahidous, Ahwach, and Rwais, each with great diversity within their respective musical genres. For example, in Ahidous, one finds rhythms like Lmsaq, Tagouri, Amhray, and Izli, which vary from one village to another. There are also musical pieces that accompany field work, such as Tamgra, Arwa, or Tawiza, as well as wedding songs that span several days, each involving a variety of songs, some sung by women and others by men. A patient observer of the rural Amazigh world would discover an endless wealth, mirroring nature itself.

A lire : Ahwach, the Amazigh tradition of Morocco

Unfortunately, this cultural richness is dying year after year. We are losing all these songs, rhythms, and customs, just as we are losing our kasbahs and ultimately our language. Everything that constitutes Amazigh culture is neglected by the state, except when tourist interests are at stake. In such cases, our culture becomes a folkloric attraction, and our soul escapes because it cannot find its vital space or truth there.

The diversity of Moroccan song and music originates from this Amazigh culture, despite the abandonment and lack of recognition by authorities, and even despite the artists themselves. For instance, there are those who advocate for the concept of Arabo-Andalusian music, which originally is Moroccan Amazigh music from El Gharnati, found in Northern Morocco and Algeria, even before it was interpreted in Arabic. Algerian singers like Dahman Alharrach, Alaanqa, and Maatoub Lounes, among many others, illustrate this truth.

El Gharnati refers to the music originating from the city of Granada in Spain. In 1492, Muslims and Jews, expelled from Granada after the Reconquista, settled in various cities in Morocco: Fez, Oujda, Tetouan, Rabat. They brought with them their literature, cuisine, customs, and most importantly, their music: Gharnati music.

Traditional Amazigh music is known for its long poems accompanied by rhythmic instruments such as the bendir and drum. This genre of music is found in arts like Ahwach, Ahidous, Regda, Rekza, performed by groups like Imdyazen and Rways, and Chyukh, who add special musical instruments, such as the flute in the Rif, the Ribab in the Souss region, and the Luthar in the Middle Atlas.

Moha Mallal – The Amazigh music scene in Morocco is very rich, and to better understand it, one must distinguish between its two major currents: traditional music and modern music, as well as observe its vast and diverse geographical distribution.

The Amdyaz (plural imdyazen) refers among the Berbers to an itinerant poet, singer, or musician. Considered a central figure in Amazigh poetry, they are seen as a chronicler and historian of their society. During their travels from village to village, they convey various targeted messages aimed at highlighting current events. (Source: Wikipedia)

The music of the Middle Atlas holds a significant place in daily communication, resulting in a prolific production of songs. Ahidous has given us great singers such as Amlal Qddour, Bnnasr Oukhouya, and Hadda Ouakki, and more recently Med Rouicha and Med Mghni. They have created melodies accompanied by the luthar or violin. However, music from the Middle Atlas remains embedded in well-defined rhythms, and there is still anticipation for new ideas to modernize this style.

In the southeastern region of Morocco, known in Amazigh as Assamer, musical art has only known the rhythm instrument called the bendir. The geographic location of the region, situated between the Souss and the Middle Atlas, has allowed both musical influences to resonate with its inhabitants.

Assamer, in Amazigh, is a place or an area exposed to the sun, where villagers gather during winter days. It has become, by extension, a place for discussing matters concerning tribes and the daily lives of families and residents. Since the southeastern part of the High Atlas, from Ouarzazate to Errachidia, is always exposed to the sun, this region has been designated by the name Assamer. The Jews call it Achamr. (Source: Moha Mallal)

Modern music emerged with young singers from the Souss region like the group Ousman, Ammouri Mbark, and Izenzaren during the height of the Ghiwane movement. Later, in the Rif region, young artists influenced by Kabyle music emerged, such as Walid Mimoun, Itran, and others who appeared in the late 1980s, like Khaled Izri, Imtlaa, Numidya, and Allal Chelih.

In the southeastern Moroccan region of Assamer, modern music only began in the early 1990s when I myself created the first recording studio, Azawan Sound, and my own music group, Mallal. This launch was the seed of modern music in the southeast, featuring singers like Hemmu Kemus and others who would arrive later such as Nba Saghru, Tawargit, Amnay, Angmar, Luland, Khaled Badraoui, Tasuta n Imal, and Tarula.

Others today are taking over to continue the traditional tunes of Tamdyazt (Amazigh poetry) since the 1970s, such as Ouhachem, Chikh Yousf, Chikh Zaid, Med Ijoud, Elhoussaine Kheyi, and many others.

Modern Amazigh music appears in two ways: the first attempts to work with traditional Ahidous tunes by introducing modern instruments, and the second works with a more universal approach in terms of instruments and the composition of poetry and music.

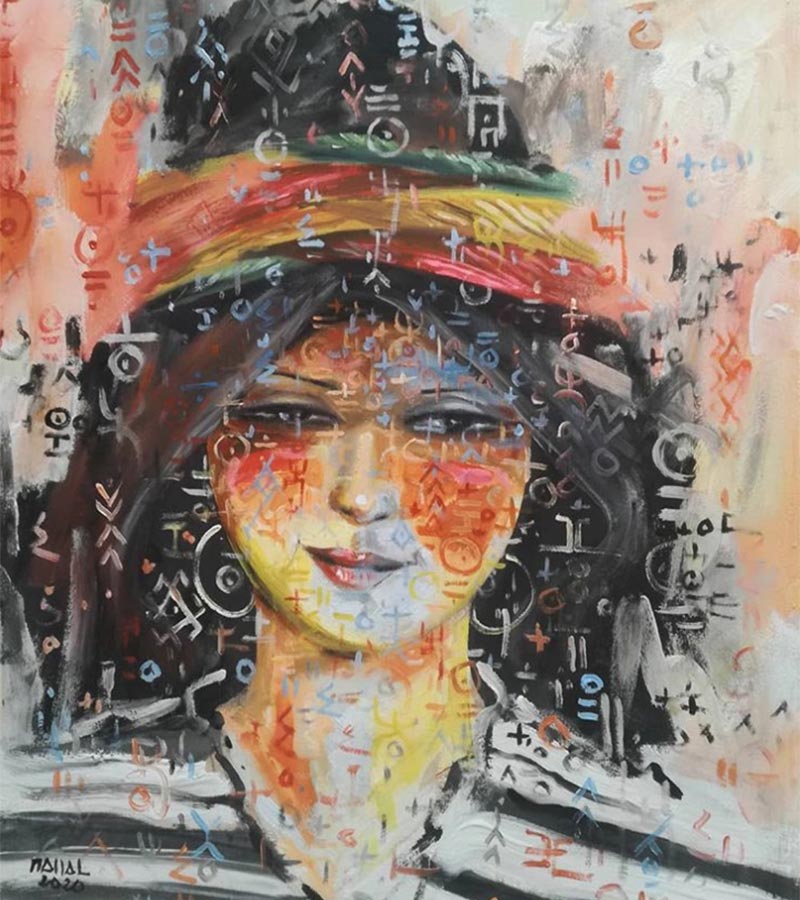

The music, songs, and traditional rhythms specific to our region create a whole that imposes itself on everyone. The cultural awareness of artists from Assamer gives our Amazigh music a personal touch, a true uniqueness linked to our territories. This realization has led us to want to give a name to this musical particularity, and we have chosen to call it Amun Style.

Moha Mallal – Amun, or Tamunt, signifies “union” in our Amazigh language. Historically, Amun was the first god of the pharaohs, the deity symbolizing unity and unification. Some ruins of the Temple of Amun still appear today in Siwa, in southern Egypt, where Imazighens (Amazigh community) live in the Siwa Oasis. This reminds us that the pharaohs are originally Amazigh.

Amun or Amon is one of the principal deities in the Egyptian pantheon, the god of Thebes. His name means “the Hidden” or “the Inconceivable” and reflects the impossibility of knowing his “true” form. It was during the Greek archaic period that the Egyptian Amun was assimilated with the Greek deity Zeus. It was the Cyreneans who introduced him to the Greek world as Ammon-Zeus. (Source: Wikipedia)

When I thought about giving a name to the musical style we were developing in Southeastern Morocco, I shared with Nba from the Saghru group the idea of using the concept of Amun.

Our intention was for our music style to stand out from others, so it needed a name that both unified all modern music styles of Assamer and carried a strong meaning. The concept commonly used to explain our music style could have been fusion, but this word did not fully meet our expectations.

Amun Style is first and foremost about the beautiful Amazigh language. It is not necessarily protest music, but rather a constant exploration in musical composition and the utilization of our entire cultural heritage.

That being said, the idea has not yet been widely accepted by most singers, especially among the younger generation, but I hope that we can establish the concept of Amun Style through the quality of our work and its exemplary nature and ability to inspire.

Amazigh music is in search of beauty

Moha Mallal – As in all civilizations, we observe artistic diversity. Each person fights their battle according to their cultural level, country, culture, and field of creation. In general, we see that political songs prevail among peoples who are victims of ideological invasion and who cannot freely live their culture, identity, and traditions. This has been evident in the birth of major global music movements such as Reggae, Blues, and Jazz. In all these cases, there is an expression of cultural and therefore identity resistance.

Amazigh music is marginalized in festivals and media, and it does not receive the encouragement that is given to Arabic or foreign music. Take Moroccan radios for example, which broadcast a wide variety of songs in all languages of the world, except the language of the country itself, namely Amazigh. Is it a coincidence that this situation of marginalization has persisted since independence?

The few songs aired on Amazigh television are folkloric songs, presenting a limited, even negative, view of Amazigh music. Then they try to portray the music sung by young Amazigh people as always politicized, when in truth this music touches on all themes of life, as is the case in all other countries. We sing about love, society, culture, and philosophy, and we do so with a great pursuit of beauty, both in terms of lyrics and music, which we aim to make universal.

Moha Mallal – Idir’s influence is strongly felt on the style of many artists from North Africa, and possibly elsewhere. The simplicity of his musical style quickly resonates with listeners, as does the joy of his words drawn from Kabyle culture and the ancient stories that grandmothers tell their grandchildren by the fireside. Personally, Idir has played a significant role in my artistic creation and in the love I put into making music and singing since 1983.

Moha Mallal – The Amazigh culture is inherently a space of harmony and tolerance. It is not Amazigh culture that could prevent the meeting and complementarity of cultures in Morocco, but rather those who refuse to recognize Amazigh culture as an original culture of the country, a culture that should be preserved at the same level as other cultures within Moroccan heritage. As long as the Imazighen are marginalized in every sense of the word, I do not see possible complementarity or cultural democracy. We, the Amazighs, speak other languages than Amazigh, study languages far from ours, sing in other languages, without any complex. But do others do it too

« I cannot accept that someone wants to make me into someone I am not »

Idir

However, Amazigh music in all its diversity is fully part of the international repertoire of civilizations’ music. And this entire repertoire, even if it legitimately echoes human wounds, is also there above all to offer the pleasure of sharing these cultures and discovering the humanities that are expressed through them. The humanistic message of this repertoire cannot be neglected, especially with the technological modernity that accelerates exchanges and thus encounters.

Harmony will ultimately be achieved one day thanks to the common will of all young artists from Morocco and elsewhere, Amazigh or not, in the respectful sharing of their linguistic and cultural diversities.

Find out more …

Mohamed Mallal, born in 1965 in Tamlalte, a village located near the Grand Dades at the entrance of the Dades Gorges in Boumalne. He holds a bachelor’s degree in history of civilizations.

He is:

- Professor of visual arts in Ouarzazate.

- Poet, composer, and performer.

- Painter, watercolorist, caricaturist.

- Writer of two collections: “Anzwum” (Concern) and “Afafa” (Awakening); “History of Plastic Arts in Morocco” is in the process of being printed.

- Screenwriter.

- He has participated in various exhibitions, workshops, and music concerts in Morocco and abroad.